Gesine Manuwald looks at where ancient texts in modern editions come from.

Autographs?

If one would like to learn more about the composition process of modern authors, in many cases one can look at autographs (original manuscripts) and see what these writers wrote first, how they crossed out material and what kind of changes they made over time (autographs for many famous British authors can be found in the British Library).

A manuscript of Wordsworth’s ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ from the British Library (© The British Library Board / Public Domain)

If one opens modern editions of texts by ancient authors, it might seem that these texts have come straight from their studies—and yet autographs of literary texts do not survive from the ancient world. All that is extant are inscriptions on stone or texts like letters written on wood or wax tablets. Thus, one is prompted to ask whether we can find out more about the journey of ancient texts to the format in which they are read today.

A Roman reads a papyrus scroll, as depicted on a Roman sarcophagus from the gardens of the Villa Balestra in Rome (public domain)

This lack of autographs also applies to the famous Roman writer and politician Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BCE). Since he wrote a large number of letters to friends and family, in which he talks, among other things, about his literary works, there is at least information on some aspects of the composition process. These letters reveal, for instance, that Cicero had recourse to the written works of others to establish facts (e.g. Cic. Att. 6.2.3), that he changed his mind on the structure of a piece while planning it (e.g. Cic. Q Fr. 3.5.1–2; Att. 13.12.2–3; 13.13.1; 13.14.1; 13.16.1–2; 13.18; 13.19.3–5), that he tried to make corrections to works already released when errors were noted (e.g. Cic. Att. 12.6.3; 13.21.3; 13.44.3) or that he justified the wording chosen (e.g. Cic. Att. 7.3.10). Yet, these considerations have not always made their mark on the texts as transmitted.

Bust of Marcus Tullius Cicero from the Musei Capitolini in Rome (José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY-SA 4.0)

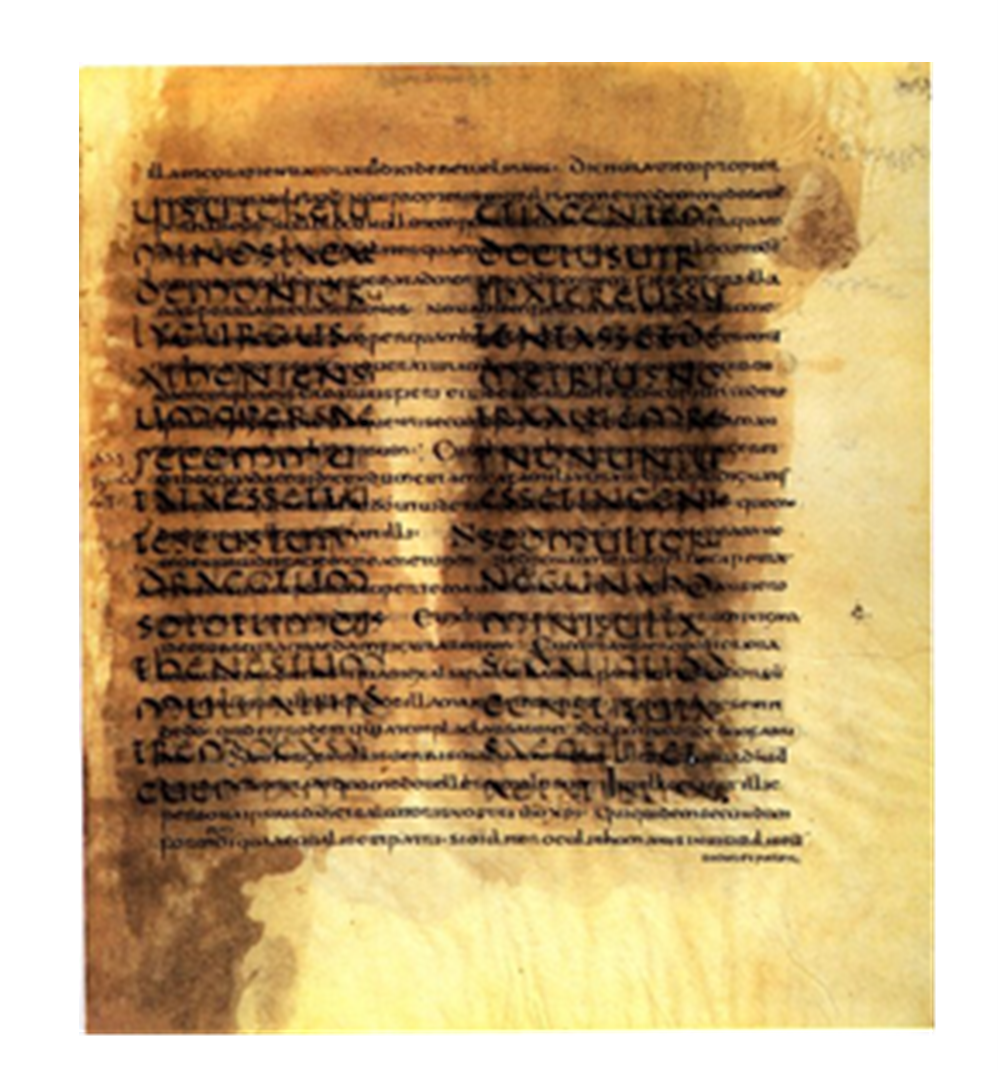

The texts available today only survive because Cicero (like other Roman writers) sent hand-written copies to friends, and they may have made copies to send them on. At least since the Augustan period there were also libraries and some form of bookshops, which facilitated wider access to texts. After Cicero’s death there was still enough interest in him as a man and as a writer so that new copies of his works were continuously made throughout late antiquity and into the Middle Ages. A few items were forgotten, however. Some of the collections of letters were not available for some time: a manuscript copy of Cicero’s letters to his friend Atticus (Epistulae ad Atticum) was re-discovered by Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch, 1304–1374) in the cathedral library of Verona in 1345; some of these letters are rather personal, and their renewed availability significantly changed the current image of Cicero. His work on political theory, De re publica (‘On the state’), was lost for even longer and was only recovered in the early nineteenth century (1819) by Angelo Mai, custodian of the Vatican Library, on a palimpsest (i.e. a re-used manuscript): he found large parts of De re publica in a manuscript beneath the writing of the text of a commentary by the church father Augustine on Psalms 119–140.

Cicero: De re publica, palimpsest (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, cod. Vat. Lat. 5757, fol. 277r) (public domain)

Preservation and distribution by means of copying and re-copying hand-written manuscripts (with all the mistakes this process may entail) continued until the arrival of the age of printing in the late fifteenth century. This period coincided with the Humanist era, when there was a renewed interest in antiquity and learned scholars in many countries made efforts to rediscover texts from the ancient world and looked for hidden copies in libraries throughout Europe. The first printed edition (editio princeps) of an author was established on the basis of these copies. These editions, for the first time, could be based on more than one manuscript, and the use of printing rather than hand-writing significantly facilitated the spread of texts. The first edition of all of Cicero’s works was the one prepared by Alexander Minutianus (c. 1450–1522), first published in Milan in 1498/99 (followed by later re-prints). This edition was based on several different manuscripts, but did not yet include text-critical notes.

Cratander and Cicero

An important next stage in the development of early editions of Cicero is the complete edition published by Andreas Cratander (c. 1485 – c. 1540) in Basel in 1528, since it is based on a progressive handling of the text and an innovative approach to techniques of textual criticism.

Andreas Cratander (a Greek-based version of the original German name Andreas Hartmann) was a successful printer in Basel (Switzerland) in the early sixteenth century. Basel was then a centre of intellectual exchange and printing activity, and so found a constant demand for up-to-date scholarly editions. Cratander first ran a printing shop in Basel and later worked as a bookseller. His printing house produced prints of more than 200 works, particularly of texts in Latin, but also in Greek, German, French and Hebrew; these publications consisted particularly of Humanist school editions and new editions of ancient authors.

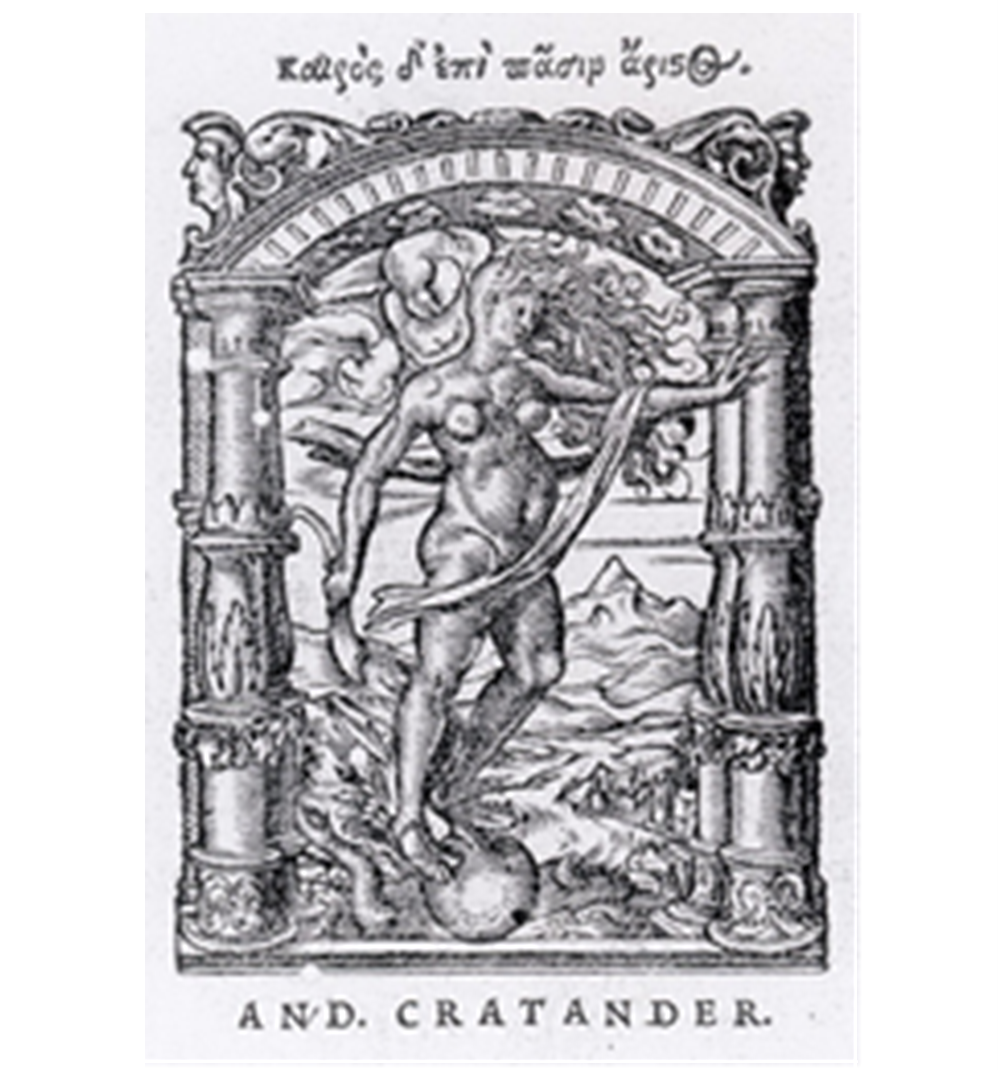

Printer’s device for Andreas Cratander, designed by Hans Holbein the Younger, from the Kunstmuseum Basel (public domain)

The Cicero edition is distinctive in a number of ways; this is partly clear from its structure and layout and partly from the preface (in the form of an introductory letter to the dedicatee of the edition, the diplomat and official Ulrich Varnbüler) and other notes in which Cratander explains the principles used. Firstly, the edition stands out by its comprehensive nature. It consists of three volumes, running to almost 2,000 pages altogether, covering all of Cicero’s works known at the time as well as others attributed to him as well as texts about Cicero (e.g. biographies) by ancient and contemporary authors. Secondly, Cratander tries to make his edition as accessible and helpful as possible to a wide range of readers: for instance, it provides glosses for Greek terms that appear in Cicero’s works and includes commentary notes on the content, presented in a separate section for the sake of clarity.

Thirdly and most remarkably, the edition is based on a novel scholarly approach to the text. Cratander made sure that he got access to as many manuscripts as possible, with the help of friends travelling to (or based in) other towns and cities in what is now Germany, Switzerland and France, providing him with information about these manuscripts. Thus, Cratander, supported by the editorial team in his workshop, was able to compare different versions of the text and to establish similarities and differences between various versions of the transmission.

The process of assembling and comparing manuscripts is still regarded as a key element of textual criticism and is necessary in establishing a reliable text today, but it was not yet standard in the early modern period and could not really be applied when texts were copied by hand from one manuscript to another. Importantly, Cratander explains this method in his introduction and also outlines the rationale of what to do when one is confronted with conflicting readings in the sources: he puts one reading in the text, adds a note marker to this word, repeats this sign in the margin and adds a note next to it, giving an alternative reading (with or without further explanation).

In the prefatory letter Cratander describes this method as follows:

‘But where by chance because of the diversity of faults there arose the difficulty in selecting the meaning, we have in those cases left those passages with letters attached to act as markers, so that a reader of sharper judgement can investigate them and compare them with his own ideas … Moreover, I decided not to follow traditional practice and indulge idle ostentation by scattering little marginal textual annotations, words, shrewd statements and notable phrases in the area around the text; we believed that it would be preferable to an eager reader if we collected whatever minutiae there were into a single index, laid out in a clear structure, to facilitate the finding of whatever we wanted. But places where the manuscripts differ amongst themselves—as happens frequently—have been marked in the margin in our usual way so that, with both readings placed in front of their eyes, anyone could follow what he thought most reasonable and make his judgement more precisely’.

(Attamen sicubi forte propter mendarum diversitatem eliciendae sententiae difficultas suboriebatur, reliquimus tum ibi eos locos, praefixis literarum formis, signi vice, lectori acutioris iudicii excutiendos, & coniectura colligendos. … Insuper non libuit margineas illas annotatiunculas historiarum, vocum, scite dictorum, & insignium loquutionum, pro recepta consuetudine, vana ostentatione, e regione contextus adspargere: sed duximus cupido lectori potius probatum iri, si quicquid id est minutiarum, in unum indicem, certo ordine digestum, congereremus, quo in promptu sit quidvis inveniendi facultas. Verum ea in quibus alicubi variabant codices, id quod plerunque contigit, ad marginem more nostro adnotata sunt, ut integrum esset, quod cuique maxime probaretur sequi, & exactius iudicare, utraque lectione ob oculos posita).

Just as in the case of modern editions with a critical apparatus (i.e. notes under the text documenting different transmitted readings and suggested emendations) Cratander provides readers with full information on the transmission accessible to him and enables them to see it for themselves and make their own decisions on the most plausible text. In this way Cratander, even though he was not the first to publish a printed edition of all of Cicero’s works, produced an edition that was an important milestone in scholarship because of the progressive methods he applied. At least one of the surviving copies of the print clearly met the needs of the envisaged readership and was carefully studied: the copy preserved in the University Library in Basel belonged to Martin Borrhaus (1499–1564), professor and twice rector of the University of Basel, and bears a large number of his hand-written annotations, especially on works that intersect closely with his own interests in rhetorical theory.

From ancient autographs to modern editions

Cratander’s edition is no longer used as a convenient edition of the text of Cicero’s works although it is available online and in a recent reproduction. Yet the principles adduced in creating this edition, further refined and developed, are still at the heart of modern editions, whether in print or in digital format, even though there is not always a direct or obvious link. It is always worth remembering how much work has gone into every current edition of an ancient text, both by the individual editor and over the course of the history of scholarship on which today’s editors build. What we read today is not the autograph, but it aims to come as close as possible to the original words in so far as they can be reconstructed, with any changes by editors indicated. Modern editions of this kind also make the reading of ancient texts a great deal easier than it would otherwise be.

Among other things, Gesine Manuwald researches on the works of Cicero and their reception in the early modern and modern period. Together with Cédric Scheidegger Lämmle she has recently completed a substantial introduction to a reproduction of the edition of all Cicero’s works, published by Andreas Cratander in Basel in 1528