Sander Goldberg on the business of writing a commentary on Terence

Scholars have hitherto regarded the Supplices as the earliest extant play of Aeschylus; if we now consent to put it late it makes all attempts to study literature futile.

F. R. Earp, Greece & Rome 22 (1953) 119

He [Aeschylus] has certain favourite images and fields of imagery to which he has recourse again and again because he likes them, because they are lodged in his mind like bacteria in a well, because they continue to be appropriate, not because he wishes to recall some earlier passage or prepare for some later one.

M. L. West, Gnomon 59 (1987) 195

Classicists were not quick to embrace what anyone outside the field would recognize as literary criticism, but we did eventually manage it. The realization that sensibilities and techniques honed on the study of modern literary texts could be applied with profit to ancient ones opened the study of Greco-Roman antiquity to an ever-expanding range of questions and broadened its appeal to an ever-more diverse range of students, none of whom would today think for a minute that the ultimate goal of literary criticism was to establish a chronology or that a critic’s work was necessarily limited to an author’s intention. This increased sophistication in our approaches to ancient texts and the societies that created them has been highly productive but remains dogged by a longstanding pedagogical unease. The old complaint was that literary Classicists—particularly, it was said, those on my side of the Atlantic—lacked “proper” knowledge of the languages, not an entirely unjust suspicion of those who, like me, came late to Greek and even later to Latin. In my case, time spent with Brooks and Warren’s Understanding Poetry was not spent with Denniston or Smyth, and I entered the profession neither well equipped nor very interested in settling ὅτι’s business or properly basing οὖν. When you are young, ambitious, and hell bent on thinking big, the value of thinking small can be hard to appreciate as old skills are cast aside in pursuit of new endeavors.

Did it matter? The Oxford historian on my dissertation committee thought so. He abandoned me to my American advisors after reading the chapter on Menander’s Epitrepontes, which began with a quotation from Oscar Wilde. A later text, he claimed, could not be used to elucidate an earlier one. What really unsettled him, though, seems in hindsight to have been not my focus on recognition as a dramatic device or the use of later examples to gauge the capabilities of earlier ones. It was the reluctance—he may have feared the inability—to engage somewhere along the line with the nitty-gritty of text, to take an interest in the distinction (if there was one) between perfect and aorist tenses in fourth-century Attic or the conditions under which Menander would tolerate a “split” anapaest. The concern was not entirely misplaced. Only now, more years later than I care to count, has the value of philological knowledge for literary investigation grown clear to me, a clarity that has come less through work as a literary critic than by taking up that most hoary of philological activities, the writing of commentaries.

Commentary writing can seem both technically demanding and intellectually constraining, but that gives it one great advantage over interpretive criticism: it doesn’t require a thesis. In fact, it’s probably better, at least at the start, to be without one as the commentator steps back and thinks primarily about what a reader needs to be told to make sense of things. The text itself then sets the agenda. This means in the case of Roman comedy, where the surviving texts are remnants of plays written for performance under particularly demanding circumstances, that how characters speak and what they do while speaking become as essential to the explication as what they say. The commentator must be a good listener and a good visualizer, laying out each scene in the mind’s eye to understand what the text implies and the action demands. The need to think dramatically, though, does not preclude the need for close reading to seek out the clues to action and emotion embedded in texts that rarely include a specific stage direction.

In the particular case of Terence, the results of such reconstructive reading may well surprise us. Terence is, after all, a playwright long respected for the lucidity of his language but not widely praised for his dramatic sense or his originality. He appears to lack the verbal fireworks, the energy and comic edge (Caesar famously called it vis) of Plautus, and his reputation has suffered accordingly—and perhaps unjustly. For example…

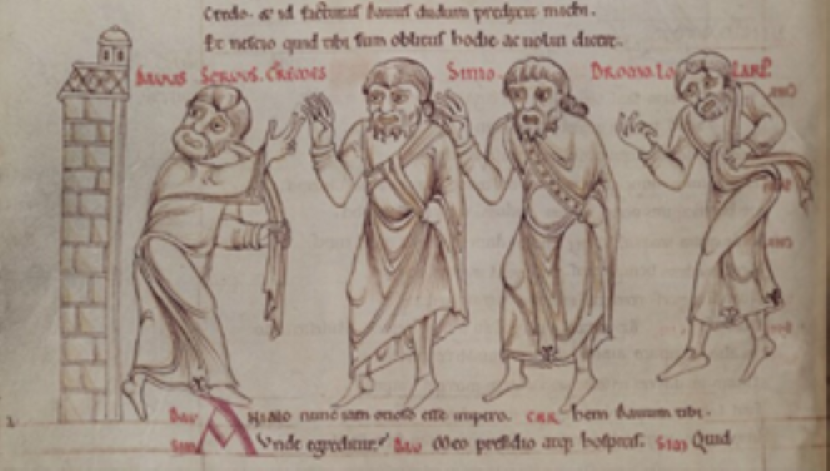

As Andria moves toward its climax, Simo’s annoyance with the pesky slave Davos, who has consistently sought to forestall his son’s marriage to the daughter of Chremes, reaches a head when Davos claims (truthfully, as it happens) that the girl from Andros whom Pamphilus loves is in fact an Attic citizen. Simo will hear none of it and commands the thuggish Dromo to haul Davos off for punishment (An. 863-70). Here is John Barsby’s version of that moment in his Loeb edition of the play.

DAV If you discover I’ve told a lie, put me to death.

SIM I’m not listening. I’ll give you a real stirring up.

DAV Even if all this is true?

SIM Even so. (to Dromo) Make sure he’s tied up and guarded, and (do you hear

me?) bind him hands to feet. Go on then. (to Davos, as Dromo carries him into

Simo’s house) As sure as I live, by heaven, I’ll show you how risky it is for you to

deceive your master, and him his father.

CHR (to Simo) Oh! Don’t be so harsh.

SIM Oh, Chremes! How’s that for filial duty? Aren’t you sorry for me? Suffering

so much trouble for such a son!

The action is apparently so vicious that even Chremes objects to it, but the accompanying dialogue sounds oddly matter of fact. That is because translation tends to flatten the contours of Terentian language, reproducing its content without its texture, so let’s instead look more closely at the original.

ia8 DAV si quicquam inuenies me mentitum, occidito.

SIM nil audio.

tr7 ego iam te commotum reddam.

DAV tamen etsi hoc uerumst?

SIM tamen.

ia8 cura asseruandum uinctum atque (audin?) quadrupedem constringito. 865

ia6 age nunciam. ego pol hodie, si uiuo, tibi

ostendam erum quid sit pericli fallere,

et ĭlli patrem.

CHR ah! ne saeui tanto opere.

o Chreme,

SIM pietatem gnati! nonne te miseret mei?

tantum laborem capere ob talem filium! 870

We are, of course, now looking at verse, a frequent stumbling block for translators (and readers) of Terence, and with the fact of verse comes a reminder—not always easy for us to absorb—that Roman comedy was a form of musical theater. Here even a cursory glance will recognize dramatic significance in the shifts between the iambic and trochaic rhythms of lines set to the tibia until, after 865, the piper falls silent as accompanied song yields to unaccompanied speech for Simo’s triumphant coda. If we recognize metrical lines as discrete units of sense, Simo’s insistence on getting in the final word at 863 and 864 emerges as a characterizing trait, while in 868, elision at the two changes of speaker shows Chremes’ eagerness to intervene and Simo’s correspondingly prompt refusal to let him. Scansion reveals further calculated effects. At 864, the characteristic conjunction of word and metrical boundaries (diaeresis) after the fourth foot of the septenarius not only coincides with the change of speaker, but highlights a repeated rhythmical pattern (˘˘ ‒ | ‒ ‒ ¦ ‒ ‒) to suggest Davos’ insolence in echoing his master until Simo (characteristically) cuts him off in the final foot. Meter thus works in the interest of character. It also enhances stage action. Simo initially ordered Davos lifted up and carried off at 861 (sublimem intro rape hunc quantum potest), but despite that demand for haste, Dromo, a slave charged with the disciplining of fellow slaves, evidently takes no action until 865…and what action is that? A clue comes with the change of meter. Adding one element at the front of line 865 sets this moment apart by turning a trochaic septenarius into an iambic octonarius, which in Terence has a regular caesura after the ninth element. That puts a slight pause after audin, lending emphasis to the operational word quadrupedem, itself noteworthy for its choriambic shape in this heavily spondaic line. This must be the moment when Dromo begins the binding, with Davos lifted up and carried off—either by Dromo alone or by unspecified silent helpers—as the music stops.

These are, admittedly, only small points of detail, but they look to a much larger issue. The traditional problem that long vexed Terentian scholarship was how to evaluate texts so readily mistaken for translations that a senior colleague, the product of old skills as well as old attitudes, once told me that whenever he read a play, he found himself turning it back into Greek. Our little exercise hints at how extraordinarily difficult such a conversion would actually have been: Terence’s musical texture uses rhythms and metrical structures to enhance character and action in a distinctly Latin idiom. The Attic gloss is largely illusory. But that realization only replaces one problem with another, viz. how to reconcile the technical refinement of this writing with the cruelty of a world where the physical abuse of a slave, an action often threatened but rarely so vividly staged, can be made a dramatic highpoint. If this is a serious moment, to what end? If it is meant to be laughable, who is laughing? And if, one way or another, the abuse is meant to entertain, how is Terentian comedy anything more than a distasteful relic of an alien sensibility? In this conflict between technical admiration and ideological revulsion, retreat to a philological tower, where we can safely debate whether quadrupedem is an adjective or a noun without confronting the cruelty of the action it describes, is not an option. Today’s students (much to their credit) will not tolerate that ploy, but then again, they may also have difficulty following the demonstration of Terence’s expertise and misunderstand the significance of the resulting conflict. The question of linguistic competence that so exercised my teachers remains with us. Learning the languages late, as I did, is increasingly a norm, not an exception, and late learning comes at a price. As they pick and choose among critical approaches and ever-expanding bibliographies, our students find themselves with even less time to memorize principal parts or diagram a Ciceronian period, much less master the subtleties of the iambic octonarius. They will nevertheless discover in time, as we all do, that whatever questions engage us and theories drive us, working with ancient texts requires the philologist’s knowledge and mastery of the philologist’s tools. There will always be that tricky interpretive crux or, especially as new interests take us beyond familiar canons and familiar periods, that essential text still unedited and unannotated. The necessary skills can be acquired over time, but only if the foundations for them are successfully laid from the beginning. The challenge for us going forward, then, is to instill in our students both appreciation of our predecessors’ knowledge and at least a beginner’s competence in wielding their tools. Whether eager or reluctant, we must at some point and to some degree all be philologists.

Sander M. Goldberg is Distinguished Research Professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. His publications on the literature of the Roman Republic include Understanding Terence (1986), Epic in Republican Rome (1995), Constructing Literature in the Roman Republic (2005), and commentaries on Terence’s Hecyra (2013) and Andria (2022). He is co-editor (with Gesine Manuwald) of a new Loeb edition of Ennius (2018) and with the musicologist Tom Beghin of Haydn and the Performance of Rhetoric (2007). He is a past editor of the classical journal TAPA and as Editor-in-Chief, guided the transition of The Oxford Classical Dictionary from print to its present digital format.

DISCLAIMER: the views expressed in these articles are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Classics for All