I became interested in Neoclassicism because I didn’t like it. It’s usually a good idea to investigate your dislikes, and though Neoclassicism seemed to be the opposite of everything I love about the Classics, I didn’t know much about it. I had encountered it most strikingly in the drawings based on the Iliad by John Flaxman (1795). Ubiquitous in old fashioned translations, Flaxman’s Iliad survives today on the cover of Willcock’s commentaries on Homer’s two epics, which are the most popular student editions. How could these bloodless, diagrammatic figures represent the humanity of Homer’s characters, I wondered? How could they have had such enormous popularity in their time as the perfect visual analogue of Homer’s poems? Gradually I became aware of the Neoclassical version of antiquity all around us: in the white columns of official buildings and the white statues of Greek gods hanging around in hotel lobbies; in the figures of nymphs and goddesses sold in garden centres; even on Wedgwood china tea sets. It’s the classical world as vague reference, as touch of class, all the more insidious because we hardly notice it, in spite of its anachronism. At any rate, that was how it seemed to me. This was a major part of the baggage of Classics, which I needed to confront sooner or later. As I started to learn about Neoclassicism, the inevitable happened—I started to like it; and by the time I finished writing a book about it, I was a confirmed fan.

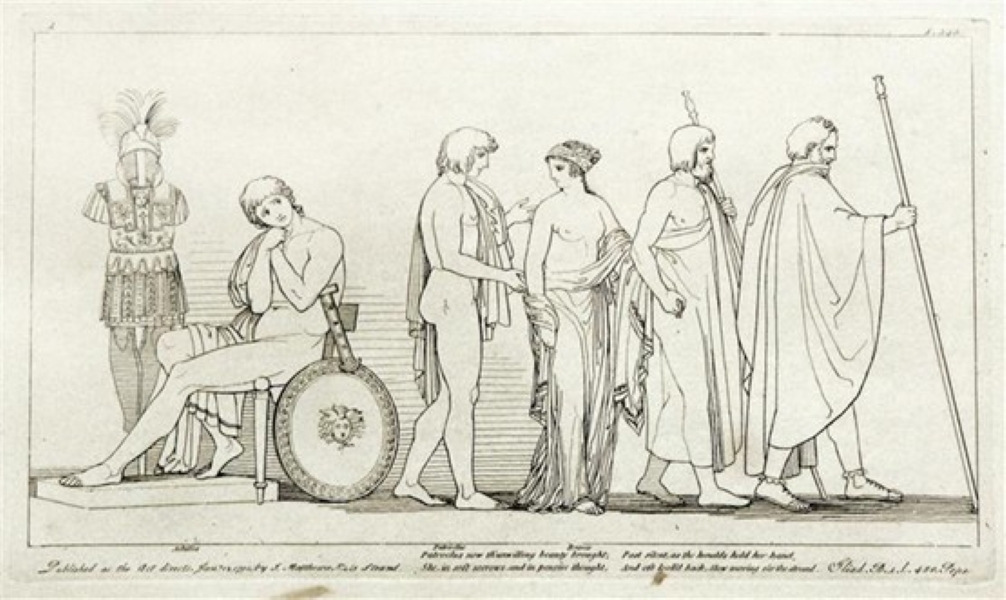

An example of Flaxman’s drawings on the Iliad: Patroclus takes Briseis from Achilles to her new master Agamemnon.

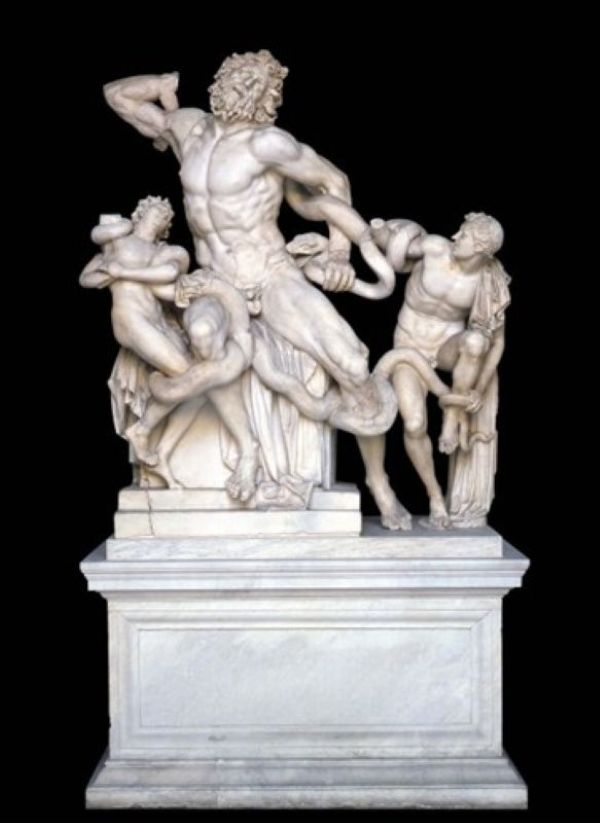

Neoclassicism is an idealisation of Greek (and Roman) antiquity which is manifested mainly in the visual arts, and particularly sculpture. More than most revolutions in taste it is the brainchild of one man, Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), a German who spent thirteen years of his life in Rome, studying Greek sculpture (or, as it turned out, Roman copies of Greek sculpture). Neoclassicism may seem boring and established now, but it started as a revolution, an upturning of what went before it, fuelled by a passionate, even erotic, engagement with the art of antiquity. It has been said that the history of classical reception is the story of a series of renaissances, in which the way forward is to be found through a renewed engagement with antiquity. This particular rebirth, unlike the early modern version, was inspired by the visual arts, not by texts. Winckelmann taught his contemporaries to see in Greek sculpture the values that he had found in it, in his famous words, ‘a noble simplicity and a tranquil greatness’. In fact, he had not seen much original ancient sculpture when he wrote his hugely influential Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1755), in which those words appear. Astonishingly, they follow an effusive description of the Laocoon, a violent Hellenistic sculpture group in which the priest Laocoon and his two sons are being strangled by a huge snake.

Laocoon and his sons

It is anything but tranquil. But Winckelmann’s revolution was about how we should look at Greek sculpture. As he said, though the surface of the sea may be whipped up by a storm, the depths are still, and what he saw in the depths of the Laocoon was stillness. Simplicity and stillness were two of Winckelmann’s watchwords, and for much of the second half of the eighteenth century artists working in all media struggled to attain this elusive ideal, to turn away from a decadent modernity, and specifically its complications and over-sophistication, in the hopes of conjuring up an idealised antiquity. But why ‘noble simplicity’? The style against which Winckelmann was reacting was the Baroque: all turbulence, colour and complexity, and it was the preferred style of absolute monarchies. Winckelmann’s ‘nobility’ was a metaphorical, aesthetic nobility, which set itself against the literal nobility bolstered by the Baroque style. Grandeur, he implied, doesn’t have to be pompous. In the wake of his writings, a flood of artwork in the style of Winckelmann’s version of Greek sculpture was produced, particularly between 1760 and 1820.

The neoclassical sculpture best known in our time is The Three Graces by Antonio Canova (1757-1822), now shared between the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the National Gallery of Scotland.

The Three Graces

In his time Canova was probably the most famous artist in Europe, though not without his detractors, then as now. The Three Graces plays variations on an ancient type, in which three naked female figures are lined up, with front and back views in different proportion depending on the side from which you approach it. Canova’s composition is more intimate, and it presents the three Graces in intimate communion with each other. ‘Grace’ was one of the qualities neoclassicists prized in Greek art, so this is an allegorical sculpture, which represents grace as a circulation of giving and receiving between his three divine figures. Canova’s first characteristically neoclassical sculpture, his Theseus and the Minotaur (1781), is also to be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Theseus and the Minotaur (Canova)

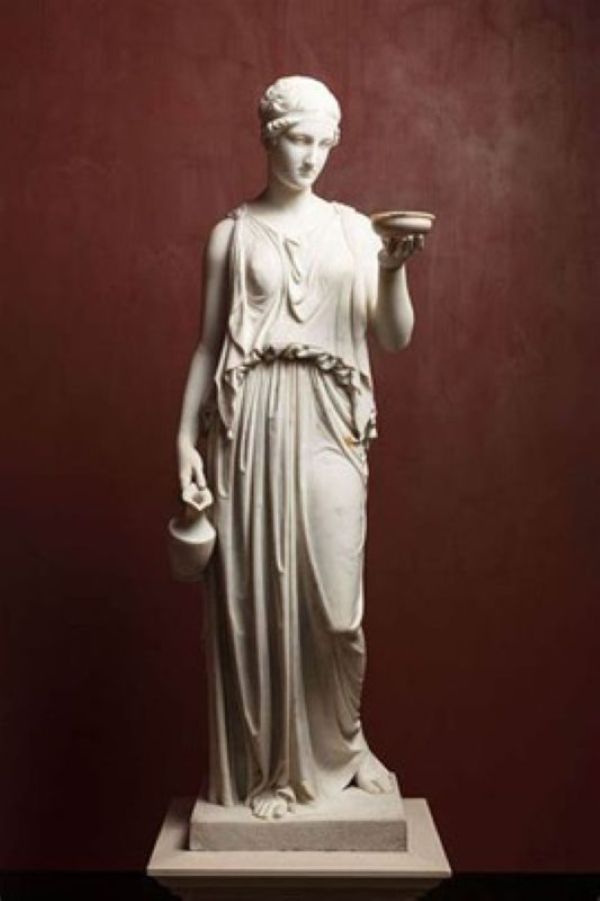

Instead of showing Theseus’ battle with the Minotaur, as a Baroque artist would have done, Canova represents him in a moment of tranquil repose after his victory, encouraging us to speculate about what is going on in his mind; his expression is as unreadable, or ambiguous, as the figures of classical Greek sculpture. For hard-core neoclassicists (though they wouldn’t have used the term neoclassical), it was a failing that Canova’s sculptures do not impose a single viewpoint on the viewer, but produce different configurations as you move around them, a sin against simplicity. For us, this complexity is appreciated as one of his prime virtues. A more strictly ‘neoclassical’ rival was promoted by some in the Danish Berthel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), whose work has none of the erotic appeal of what Canova called his ‘true flesh’, but attains a more severe tranquillity. Thorvaldsen’s Hebe (1815) could be called the perfect neoclassical sculpture: its balanced composition of stillness and movement holds our gaze as steadily as Hebe’s gaze is focused on her cup. She is the goddess of youth, who served the gods with the nectar that keeps them immortal, and she seems to exist in a state between suspended life and cold marble.

Thorvaldsen’s Hebe (1815)

Neoclasssical sculpture has been described as ‘vague white things’, and a pervasive whiteness is what strikes us most about it now. Ancient Greek sculpture was not white, but to some degree or other painted. The fact that what survived of ancient sculpture had lost its paint encouraged earlier viewers to believe that classical sculpture was white. Winckelmann and others knew that this was false, but to him what was aesthetically significant about Greek sculpture was contour. Colour he regarded as the domain of painting, which catches momentary effects rather than the eternal essences conveyed by sculpture. For this reason, neoclassical thought valued drawing more than painting, which accounts for Flaxman’s choice of outline drawing for his Homer illustrations. White, and to a lesser degree black, were the colours of Neoclassicism. Ironically, Canova was widely criticised for tinting his sculptures slightly, an effect which is now lost; like the white of ancient Greek sculpture, his hyper-white is a result of the losses of time. Ancient Greek sculpture represents naked male and female bodies, and the male bodies are as clearly eroticised as the female bodies. But for neoclassicists, the white marble sublimates the eroticism, and renders the nakedness ‘chaste’. Canova’s insistence that his sculpture is innocent of eroticism, despite its ‘true flesh’, is one of the paradoxes that makes neoclassical art so interesting.

So, learning about the issues, controversies and differences of taste within the neoclassical approach to imitating antiquity encouraged me to look again at what I had relegated to a homogeneous blob. One of the ironies that I had least expected, pointed out by a number of art historians, is the forward- rather than backward-looking aspects of Neoclassicism. Its geometrical simplicity anticipates the abstraction of modernist art, and the uncanny vacancy it conjures up has reminded some of Surrealism. In addition, a good case could be made that Flaxman’s outline drawings of Homer’s heroes are the ancestors of the superheroes of Marvel comics.

The neoclassical style spread quickly around the globe. Its unfussy simplicity was suited to the mass production of cheaper versions of luxury objects that was made possible by new industrial techniques and organisation of labour. Josiah Wedgwood’s ceramic factory brought neoclassical designs, many by Flaxman, into middle class homes. Also, the Napoleonic wars in Europe called for memorials, and this instantly recognisable style, conjuring up an idealised antiquity, was the obvious choice for memorialising the heroic dead. The products of Neoclassicism are still with us today, though its version of antiquity was swiftly overtaken by one inspired by the violent extremities of Greek tragedy and the fragmentary state of surviving examples of original Greek sculpture. Winckelmann’s canon of great classical sculptures was soon reidentified as copies, and the sculptures he admired are now more likely to be classified as Roman. We no longer value ancient art for its ‘Noble simplicity and tranquil grandeur’, though, insofar as we can still feel the pull of that vision, Neoclassicism lingers in the subconscious of all enthusiasts of the ancient world, as its products linger in our public environment.

William Fitzgerald is Professor of Latin Language and Literature Emeritus at King’s College, London. Among his many publications are: The Living Death of Antiquity: Neoclassical Aesthetics (Oxford, 2022), How to Read a Latin Poem: If You Can't Read Latin Yet (Oxford, 2013), Slavery and the Roman Imagination (Cambridge 2009) and Martial: the World of the Epigram (Chicago 2007).