In its main currents, the poetry of the Western world, from Homer to the present day, constitutes a unity. And the citation of Homer in the ‘from’ part of that proposition points not only to the fact that the Homeric poems constitute the attested opening of the sequence, but also to the distinctive place of classical poetry, Greek and then Latin, within the sequence: in some eras, a model; for many individual poets, a special point of reference; for Western poetry as a whole, an effective archetype.

Correlatively, theoretical understandings of Western poetry should aspire to have regard for the unity as such. Not regard for every stage in every language, of course: there are far too many stages and languages involved. But regard for the unity as such – which means, above all, a willingness to take account of the archetype, alongside whatever is felt to be of particular or representative significance in the millennia since. This is not how most modern theorisers go about their business, especially in recent decades. Rather, the poetic corpus that is put forward as the basis of the theorising is liable to be selected modern poetry from one modern language, with or without some gesturing towards earlier literature or literature in another language, ancient or modern. But regard for the unity as such: that should be the aspiration.

Correlatively, too, it makes sense for any theorist to have regard for the theorisings about poetry that have been formulated, or followed, down the centuries, from Aristotle and Horace in antiquity to the theoretical concerns of the modern world. That is certainly not the usual pattern. Recent or contemporary theorists tend to look no further back than the modern age itself: to the admirable Russian Formalists, in the opening decades of the twentieth century: to the perceptive discussions by literary Modernists like William Empson and the American New Critics; to the often challenging sophistications of French poststructuralism. As my epithets indicate – ‘admirable’, ‘perceptive’, ‘challenging’ – these and other modern movements, and other unclassifiable individuals, are of special importance to any contemporary theorist, not actually because of their modernity, but because of their distinction. It has to be said, though, that if one’s concern is poetic language, some individuals and some movements are unlikely to be of central importance (postructuralism, in particular, except on a problematic meta-level: Genette’s 1972 essay, ‘Valéry et la poétique du langage’, is representative here – see my critique in ‘Language, Poetry and Enactment’, Dialogos 2, 1995). Conversely, it does makes sense for any theorist to be alive to the possible importance of theoretical formulations from any period and any age.

The book I am currently writing – now nearing completion – is conceived on this basis. It represents an attempt at a theory of poetic language, with particular reference to what I take to be poetic language’s two irreducibly important aspects, elevation and heightening (see below). The title is Poetic Language in Theory and Practice: Greek Archetypes and Modern Dilemmas (Oxford U.P., forthcoming). The book ranges across Western poetry, from then to now, and discusses in particular detail examples of poetic ‘practice’ from ancient Greek to modern English – from Euripides and Pindar to Eliot and Yeats, Ted Hughes and Benjamin Zephaniah – along with examples from French, Italian and German: notably François Villon in the fifteenth century, Friedrich Hölderlin at the turn of the nineteenth, Eugenio Montale and Paul Celan in the twentieth. More unexpectedly, no doubt, I consider at length the language of the standard American popular song, in the lyrics of Ira Gershwin and Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Johnny Mercer and many others.

The ‘theory’ in the title encompasses, itself, (pro)positions from Aristotle to those of today, but not least the reflections of significant poets, from Horace in antiquity and Dante in the late Middle Ages to Joachim Du Bellay, spokesman of the French Pléiade in the mid-sixteenth century, to Hölderlin’s English contemporaries, Wordsworth and Coleridge, to ‘the national poet’ of modern Greece, Dionysios Solomos, to (not least) Eliot and Yeats, again. Above all, though, the theory is my own, and centres on an essentially new argument about heightening and elevation, in the comparative perspective indicated.

Among the chief characteristics of classical Greek verse, and then Latin verse, especially ‘serious’ verse, is its elevation. Anyone learning to read Latin or ancient Greek soon discovers that the language of the poets has distinctive characteristics. As the orator Isocrates put it in the fourth century BC, ‘the poets are allowed to do all sorts of things which we orators are not’ – and, he goes on to note, the poets use, among much else, what he calls ‘exotic expressions’ (ὀνόμασιν . . . ξένοις: Evagoras 8). In his Poetics (ch. 22) and Rhetoric (III), some years later, Aristotle develops the point.

Isocrates’ ‘exotic expressions’ constitute one kind of elevated language on the poetic surface. Surface elevation tends to involve conventional stylisation. It may mean verse words – vocabulary that is actually, or largely, restricted to verse – which, in fact, usually means inherited archaisms. ‘Sword’ in Virgil is liable to be the verse-word ensis, rather than the ordinary gladius (though he uses that, occasionally, too); ‘house’ in Euripides is often the verse-word δόμος (there are hundreds of occurrences), but never the ordinary οἰκία. οἰκία and gladius are everyday items; δόμος and ensis are not; and the use of such words stylises the language of poetry away from the everyday.

Other kinds of elevated usage work the same way. In his lyrics, in particular, a tragic poet like Euripides freely uses a noun like δόμος to refer to, not just a house, but the house, without the definite article that is the norm in fifth-century Attic. Thereby, he aligns his usage with that of his poetic predecessors, all the way back to the linguistic practices of Homeric epic, which represents a stage in the language where definite articles are not yet the norm; and this alignment in effect affirms the continuity of Greek poetic tradition, along with the special distinction of its Homeric starting-point. In Homeric verse itself, other omissions and elliptical usages (as they would be felt to be in later centuries) are likewise normal, notably the use of bare case-endings where prepositional phrases would subsequently be customary. This too is a feature of tragic usage, especially in lyrics, and its outcome is a mode of compression alien to the conversational – or prosaic – norm. Again, the word order of a tragic sequence, especially in lyrics, is liable to be freer than the fifth-century norm.

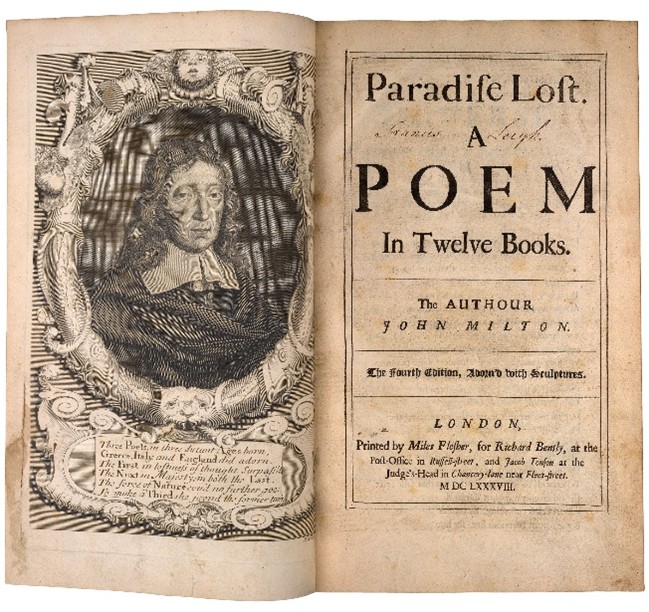

Such features – and there are more besides – are taken over into much of the ‘serious’ poetry of Western languages in later eras, beyond the end of the classical world. Or rather, equivalents of such features – because the particulars of surface elevation in one language may not be transferable to another. Post-Shakespearean English, for instance, has never possessed a significant battery of verse words: apart from the increasingly archaic ‘thou’ and ‘thy’, items like ‘nigh’ = ‘near’, ‘steed’ = ‘horse’ (now merely quaint), have always been few in number. But take the first lines of Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667): ‘Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit | Of that forbidden tree, . . . | Sing, heavenly Muse . . .’ Milton is an extreme case because he insistently Latinises his English: his very title is a kind of Latinate phrase (noun, plus past participle passive) – which in effect covers both ‘the lost Paradise’ (the garden of Eden) and, especially, ‘the loss of Paradise’ (Satan’s revenge on God). In any case, though, the opening lines of the epic exemplify the anti-idiomatic freedom of word order that ancient poetry displays, in the shape of the grand inversion: not ‘sing of man’s first disobedience . . .’, but ‘of man’s . . . sing . . .’. That ‘Sing, heavenly Muse’, meanwhile, is itself elevated in its own right. Just as a Greek tragedian’s elevated usage evokes the language of earlier poetry, Milton’s here looks back to the usage of classical antiquity – all the way back to Homer. Homer’s two epics begin, ‘goddess, sing the wrath of Achilles’ and ‘Muse, tell me of the man of many turns’. Milton’s ‘heavenly Muse’ is actually the Holy Spirit of Christianity, but the idiom is classicising and elevational in its own right.

The 1688 edition of Paradise Lost

Milton is indeed an extreme case. Consider, a century and a half later, the opening of Keats’s ‘Ode on Melancholy’: ‘ No, no, go not to Lethe . . .’ . Resist any thoughts of suicide, in other words – but Keats’s own words foreground the archaising phraseology of ‘go not’ and then the classicising ‘Lethe’, place of death, whereas, by contrast, the opening ‘No, no’ has an idiomatic immediacy. But now compare a more recent case, the opening of Yeats’s ‘The Circus Animals’ Desertion’, a poem written not long before the poet’s death in 1939, in which he proclaims his incapacity (as he presents it) to write anything new: ‘I sought a theme and sought for it in vain, | I sought it daily for six weeks or so.’ ‘Sought’ and ‘in vain’, if not archaic, feel, at least, old-fashioned. More fundamental: the three-part structure (‘I sought . . . and sought . . . | I sought . . .’) is a stylised shape, a tricolon, where the three members increase in length from the first (or, often, the first and second) to the third. ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen’, says Mark Antony at the start of his speech in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, and this elevated shape, again, goes back to antique practice. But the phrase that completes Yeats’s tricolon is quite different: ‘ . . . for six weeks or so’. The phrase impinges as not just idiomatic, but colloquial-conversational, and this usage reflects a momentous shift in modern poetry – across the Western languages – towards the normative use of the everyday. It is now common to encounter poetry composed entirely in such language, with or (often) without any stylistic flourishes:

I showed her the spare room

she thanked me several times

stripped to her bra while

I was still there.

Only those who have homes are entitled

to modesty.

(Alison Fell, ‘For Maria Burke’, 1979)

I’m not sure if Governor Cuomo’s shipment of 1000 ventilators are all

present and accounted for;

I do know it took two Chinese billionaires to breach the Great Wall

and somehow spirit them to New York . . .

(Paul Muldoon, ‘Plaguey Hill, 6’, 2020)

In these sequences there is no surface elevation of any kind, and relatedly the regular verse forms of Milton, of Keats, of Yeats, are absent, too (despite the hint of rhyming verse in Muldoon’s ‘all – Wall’), in favour of free verse and its deference to, exclusively, the rhythms and shapes of ordinary language. ‘Relatedly’, though, because it makes sense (as I argue) to think of the stylisation of verse form as itself a kind of residual elevation. Free verse has its own history – from ancient Greece (as so often) to Klopstock and Hölderlin in eighteenth-century Germany to Walt Whitman and then French vers libre in the nineteenth century, then Modernists like Ezra Pound a generation or two later – and free verse is far from homogeneous overall, but the recent tendency to normalise ordinary language within it is unmistakable. Some modern poetry, like Yeats’s ‘Circus Animals’, offers an accomodation of elevation (surface/residual) and ordinary language; much does not. Why, though, has elevation been so widely marginalised? Why was it ever the poetic norm? – as it was for millennia. Not least, what follows from its marginalisation?

These questions are at the heart of the book, and crucial for my discussion is the distinction between elevation and heightening (on which see, briefly, my chapter, ‘The Language of Greek Lyric Poetry’, in E. J. Bakker (ed.), A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language (rev. ed. 2014), 424–40). I favour these labels that, perhaps, sound like synonyms, because they have often been conflated (as they were in ancient theory), but also because they have themselves (as I argue) a determinative relationship. Heightening has been recognised since antiquity, but only properly privileged as an aspect of poetic language since the earlier decades of the twentieth century. Properly privileged: the Formalists, the Modernists, and all manner of theorists since have rightly seen that this is what gives poetry a special capability, not only to be different from ordinary discourse (as elevated language also is), but to transcend the limits of ordinary discourse and thus say, or show, more than ordinary discourse can. Heightened language is what Pound referred to, in the 1920s, as ‘language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree’, and literary theorists, and philosophers, too, have repeatedly identified the special potentialities of such language in poetry. ‘Only in poetry does language reveal all its possibilities’, said Mikhail Bakhtin in the 1920s: ‘Poetry squeezes all the juices from language, and language exceeds itself here.’ Poetry, said Martin Heidegger, in the ’30s, ‘brings the unsayable into the world’. And in the ’90s, Alain Badiou: poetry directs us to ‘what can’t be said in the shared language of consensus’.

There are many different mechanisms of heightening. Tropes like metaphor (‘the most important thing’, said Aristotle: Poetics 22), if not the most important, are, no doubt, among the most obvious. ‘The barge she sat in, like a burnished throne, | Burned on the water’ (Antony and Cleopatra, 2.2): the metaphorical ‘burned’ does what no literal usage could, suggesting, with pin-point sensuous immediacy, the visual effect of the queen’s barge on the water, but also, through the connotations of ‘burn’, hinting at the destructive potential of her royal presence. Activation of connotations, irrespective of metaphor, is a main mechanism of heightening in its own right, as are rhythmic and sound effects. ‘. . . like a burnished throne, | Burned . . .’: the metaphorical ‘burned’ (highlighted by the – so-called – rhythmic inversion: ‘thròne | Búrned’) emerges from, is prepared by, the literal ‘burnished’, which itself is prepared, more discreetly, by the innocent ‘barge’.

What I propose is that elevation – surface and residual – is the natural ground for the heightening that is rightly, now, privileged by theorists of poetry; and much of my consideration of particular examples, and my discussion overall, is designed to demonstrate this and to ponder its implications. Yes, heightening is possible without any elevation, but – so to speak – against the grain. In effect, then, a significant element of my argument amounts to a theory of elevation. No-one, in or since antiquity, has ever offered such a theory. In the centuries when Western poetry was, largely, elevated, theorists (from Aristotle onwards) simply assumed it. Since elevation has been marginalised in poetic practice, theorists have largely ignored it. Neither position is adequate.

It is important that literary criticism and theory is open to these matters – and productive scrutiny of such matters is only possible, I suggest, in the perspective of the whole sweep of Western poetic usage. Which means that awareness of the Greek archetype is a prerequisite. My book is predicated on this. In the course of my discussions, issues of ‘content’ as well as ‘style’ necessarily arise – from the socio-cultural premises of Villon’s Testament in the fifteenth century and the American popular song in the twentieth to the aristocratic allegiances of Pindar in fifth-century Greece and Yeats, just yesterday – but poetic language (and heightening and elevation within it) is the central consideration throughout.

Michael Silk is Emeritus Professor of Classical and Comparative Literature at King’s College London, Adjunct Professor in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and a Fellow of the British Academy. From 1991 to 2006 he was Professor of Greek Language and Literature at King’s. He has published extensively on poetry and drama, the classical tradition, and literary theory and thought (from Homer to Aristophanes, Sophocles to Shakespeare, Aristotle to Nietzsche, and Virgil to Ted Hughes). His publications include: Interaction in Poetic Imagery: With Special Reference to Early Greek Poetry, Cambridge U.P., 1974/2025; Nietzsche on Tragedy (co-authored with J. P. Stern), Cambridge U.P., 1981/2016; Homer, The Iliad (Landmarks of World Literature), Cambridge U.P., 1987/2004; Tragedy and the Tragic: Greek Theatre and Beyond (ed.), Oxford U.P., 1996; Aristophanes and the Definition of Comedy, Oxford U.P., 2000; Alexandria, Real and Imagined (ed. with Anthony Hirst), Ashgate, 2004; Standard Languages and Language Standards: Greek, Past and Present (ed. with Alexandra Georgakopoulou), Ashgate, 2009; The Classical Tradition: Art, Literature, Thought (co-authored with Ingo Gildenhard and Rosemary Barrow), Wiley–Blackwell, 2014; Poetic Language in Theory and Practice: Greek Archetypes and Modern Dilemmas, Oxford U.P. (in preparation: publication expected in 2026/7).