Mark Antony incites interest. When my neighbours and friends learned that I was writing his biography, they were all of them immediately animated by queries, commentary, and advice. One acquaintance, whom I'd always taken for someone right out of central casting for the part of Paragon-of-and-Old-fashioned-Respectablity, stopped me on the footpath and, in a hushed tone, insisted I must tell all - all - about Cleopatra. There was also a personal riff among some academic friends who, I discovered, had over the years bottled up some quite hard feelings regarding Cicero. Antony, I soon learned, furnished an attractive, therapeutic vent for all of them. Not that they were an Antony fan club exactly. But it soon became apparent that I was not the only one for whom Antony was something of a guilty pleasure.

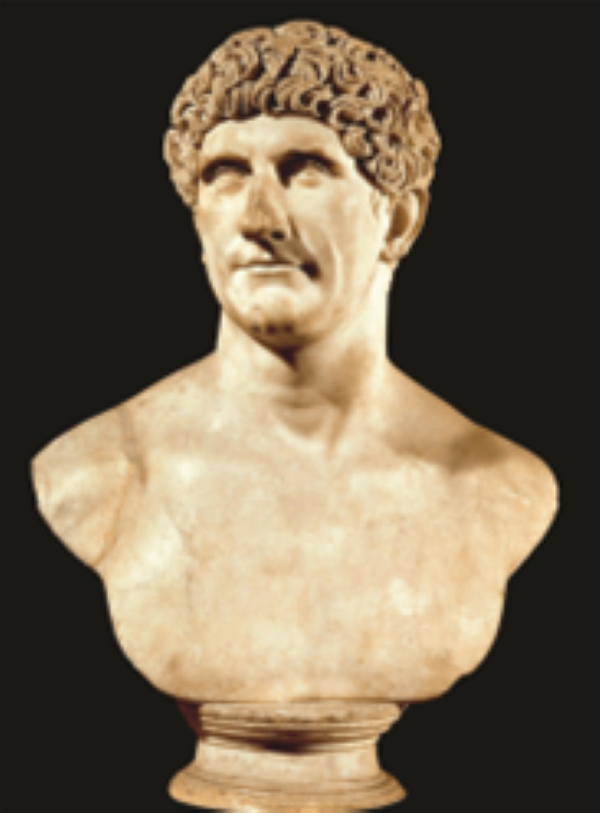

A bust of Mark Antony from the late 1st cent. AD (Chiaramonti Museum, Vatican Museums, The Vatican).

For many of us, including many ancient historians, Antony remains the chivalrous, sensual, and unstudied figure we find in Shakespeare and whom Shakespeare found in Plutarch's exquisite biography of the man. Plutarch's Antony is a strong text, perhaps the most affecting of his Lives, and for that reason it is entirely unsurprising that in Ronald Syme's The Roman Revolution, still the best and certainly the most readable narrative of the Rome in which Antony lived, we find once again an elegantly drawn version of this same Antony. This is the Antony, able but unimaginative, whose decency renders him wholly incapable of resisting Cleopatra or competing with Octavian. The latter is a figure who even now is often depicted as an nearly unerring genius possessed of preternatural cunning, flushed from the start by a fierce passion for mastery. Even if we don't believe it, we cannot fail to report how, in the end, he claimed to stand up for a righteous, nativist Roman Italy when it was threatened by a decadent, traitorous Antony at the head of an invasion of eastern, alien forces. Told this way, in a story populated by personalities like these, the history of triumviral Rome feels permeated by a grim inevitability which offers very little in the way of moral uplift. No wonder, then, that the glamour of Antony and Cleopatra so readily become a welcome distraction from this tragedy's final act, after which we must abide in this dull world.

But this is no longer how we do history—even narrative, political history. For Syme, and not only Syme, 'Roman history ... is the history of the governing class' (The Roman Revolution, Oxford 1939: 7), which is of course true but not true enough and in important ways is misleading. We must also reckon with broader and variegated social contexts, the economic, sociological, and institutional realities which Eric Hobsbwam neatly described as 'the impersonal groundswell of history on which the more obvious men and events ... were borne' (The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848, New York 1962: 5). It is not an easy balance to maintain, but we are better able to do so now than we were when Syme gave us The Roman Revolution nearly a century ago.

Our knowledge is far from perfect, and most of our claims about the past must remain provisional, but we know far more than ever before about the practical affairs, public and private, both of Romans in the west and peoples in the eastern Mediterranean. Our supply of material and documentary evidence - vital resources like coinage and inscriptions - continues to expand. The practices of Roman politics, Rome's exploitation of its empire, and the complex operations of Rome's subjects and allies, who were not without influence and clout of their own, complicate any view of the agency of Rome's (or any Mediterranean city's) governing class. As for the serious study of Hellenistic society - the triumviral east - recent decades have been boom times. Add to that the fact that the careful studies of contemporary historiographers have left us deeply sensitive to the sheer literariness of our narrative sources and mindful, in the case of writers like Plutarch, Appian, and Dio, of the imperial perspective through which their accounts of the triumviral period are refracted. All of which is to say that, in attempting to recover the history of the age and Mark Antony's role in it, we find ourselves in circumstances far more favourable than all but our most immediate predecessors.

For me, this was a great part of the attraction in writing about Antony: the chance to fill in and make more of his eastern career and to view it as something other than the moral vulnerability Octavian (and, with greater nuance, Plutarch) insisted that it was. Which is not to say that specific, concentrated work along these lines was lacking, but, where the east was concerned, there was not yet anything to rival Josh Osgood's admirable Caesar's Legacy or the rich biographies of Cleopatra by Maurice Sartre and Bernard Legras. I was—and am—excited by the possibilities offered by what, by a classicist's standards, is an abundance of specific evidence which can enrich and complicate the texture of our recovery of the triumviral period. But much remains to be done.

Cleopatra, Michelangelo, c.1535 (Casa Buonarroti, Florence, Italy).

Let me begin with a complication. Thanks to a splendid paper by Sheila Ager, published in 2013, one rarely any longer talks about a marriage between Antony and Cleopatra. At the same time, it is obvious how, during the thirties, their personal relationship developed into something which was much more than an affair or a transactional political combination. In the end Cleopatra clearly supplanted Octavia as the centre of Antony's attentions, a devotion in which he persisted to the end. We need not wax Shakespearean, but there is little point (and no genuine realism) in ignoring this personal dimension in the trajectory of the triumviral period's geopolitics. Historians and especially biographers have often located the turning point in this relationship in the winter of 37, when Antony summoned Cleopatra to Antioch, recognised his paternity of her twins, expanded her domains, and, before marching off to Parthia, left her pregnant with a son. Henceforth, a prevailing view holds, they were yoked—if not by way of marriage then by way of an affectional bond very much like it. Thereafter the politics of triumviral Rome could never be the same. Now this renewal of their liaison was doubtless significant, but, just as Antony, in the aftermath of their first winter together in Alexandria, did not return to Cleopatra for four years, and did so unexpectedly, there is no obvious reason to conclude that in 37 he harboured freshly intimate designs for their future.

In fixing this winter as the key moment, scholars routinely point to tetradrachm coins minted in Syria, some possibly even in Antioch, which depict both Antony and Cleopatra (RPC 4094; 4095; 4096). Prior to this, Antony had appeared on a profusion of eastern coinage, often, and remarkably, along with Octavia, the first living Roman woman ever to appear on a coin. These tetradrachms, minted on Cleopatra's authority (they are in Greek) but obviously with Antony's approval, mark a startling and conspicuous change: solid evidence of a kind different from drawing inferences from retrospective, sometimes torrid, imperial narratives. These coins are routinely dated to 36, which, if true, would constitute a strong argument for detecting a turning point in the winter of 37.

Tetradrachm 4094, minted 36BCE showing Cleopatra and Antony

But is it true? Antony's coinage is certainly vital for recovering his story, and it is unquestionable that by 35 or 34, in Roman and provincial coinage alike, there was suddenly an abundance of coinage portraying Antony and Cleopatra together. At about that time, Octavia, significantly, was dropped. But what about our tetradrachms and their relationship to the winter of 37? Now it is a certainty that these coins were in circulation by 33 (in that year the Parthians restamped one of them), but that is the only certainty. Numismatic studies of these coins conscientiously recognise the impossibility of dating them precisely; true, they usually suggest 36 - but do so on the assumption that the winter of 37 was the moment when Antony and Cleopatra married. This circularity, to be fair, is anything but unnatural: historians tend to consult numistatic reference works; numismatists rely on standard histories; and details can easily get lost: non omnia possumus omnes. Still, the fact of the matter is that these coins really do not help us to settle the facts of the matter. My own view is that it makes more sense to align these tetradrachms with the profusion of Antony and Cleopatra issues in 35 and 34 - and to regard the winter at Antioch as important but not a decisive turning point. Others will disagree. And we all must feel the frustration of possessing excellent documentary evidence which is too unfixed chronologically to decide this important question.

But we needn't always throw up our hands. Most of the time, material evidence from the east furnishes valuable correctives to the orientation of our literary sources, which, influenced by Octavian's propaganda and its perpetuation during the Age of Augustus, all too often give a misleading impression of the Romans' take on their eastern empire. Octavian's ferocious culture war against Cleopatra and Antony—his campaign on behalf of tota Italia—demanded that a nativist west feared the east as a threat to its way of life, and although no historian has ever taken this insistence literally, many have detected in its success evidence of Roman discomfort with the practices of Hellenistic society. All agree that Antony was never without supporters in Rome, but there is often a suggestion that even his friends may have looked askance at his eastern ways, ruffled if not repulsed by what even Plutarch denounces as oriental flummery. But first-century Rome was not so parochial as this. Modern studies, predicated on close examiantions of multiple specific situations in Italy and in the east, rightly emphasize the ancient Mediterranean's connected history, its histoire croisée, which, although it did not render Rome a thoroughly cosmopolitan place, went a long way nonetheless towards the creation of a reasonably integrated empire.

Consequently, we can no longer pretend, as Antony's enemies asserted, that Roman sensibilities were outraged by familiar features of Hellenistic pageantry. In the east, Antony fashioned himself the New Dionysus, and in dealing with Rome's dependents, including the Egyptians in Alexandria, he played the part of a grandee on a par with Hellenistic kings. Octavian would later complain that in doing so Antony was bizarrely un-Roman. But Octavian's shock is the shock of Casablanca's Captain Renault. It was a longstanding practice of Roman officials in the east to participate in the rituals of majesty which resonated there, including the acceptance of divine honours. How else to govern, really? Nor were these cultural connections limited to officials, something made clear enough by our material evidence. Investing in the provinces entailed cultivating personal as well as professional relationships which were best phrased through locally meaningful concepts. The Cloatius brothers, for instance, were rich Romans who were honoured in stone and in the Greek style as proxenoi and benefactors by Gythium, a city they both aided and profited from (SIG3 748). On Chios, the wealthy Lucius Nassius, aware of the civic importance of the gymnasium in any Hellenistic city, dedicated statues of his sons there (Chios 15). And so it goes.

The Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo ca. 1745–47

These were examples of ‘going native’ which were neither exceptional nor exceptionable, even in the view of the lower orders. In Italy and in Rome, the effects of international commerce and the movements of people (not always voluntary) rendered the west, for all the uniformity of its civic expressions, culturally more variegated than it looked. Which is not to say everybody liked it. Tacitus complained that Rome was a place where everything in the empire that was shady and shameful settled (Ann. 15.44); doubtless there were folk in the first century bce who shared his view. But most Romans understood that the Mediterranean included more than one culture and that, when in the east, it was perfectly normal for Romans to operate in an eastern style. Which is why traditionalists were not perturbed when Marcus Brutus received divine honours from the Athenians (I. Délos 1622), nor was Octavian outraged when, in the same city, his sister became a goddess (SEG 12.149).

These are only glimpses into the rich, wonderful problems of triumviral history, a vital period which demands our further investigation. I am well aware that my biography of Antony will not be the last one: Antony and his age are simply too interesting for interest to flag. We will make progress in our grasp of the big picture of triumviral Rome so long as we remain alert to the implications of all the many little pictures which emerge in the east as well as the west. But, even as the bulk of our evidence and the insights of our conceptual models improve, we cannot evade the challenge of attending simultaneously to the importance of personalities and the significance of the cultural structures within which they must operate.

Jeff Tatum is Professor of Classics at Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand). His A Noble Ruin: Mark Antony, Civil War, and the Collapse of the Roman Republic was published by Oxford in 2024. His other books include The Patrician Tribune: Publius Clodius Pulcher (1999), Always I am Caesar (2008), Athens to Aotearoa: Greece and Rome in New Zealand Literature and Society, with Diana Buron and Simon Perris (2017), Quintus Cicero: A Brief Handbook on Canvassing for Office (2018), and A History of Latin Literature from its Beginnings to the Age of Augustus, with Laurel Fulkerson (2024).