Tom Keeline looks back at Knox’s life and legacy

The story goes that when Ronald Knox was six years old, he was walking on the beach one day with his seven-year-old brother, Wilfred. Gazing out upon the briny deep, Wilfred felt a philological stirring in his soul. He turned to Ronald and wondered aloud, “Ronnie, do you consider that Xenophon’s men cried ‘θάλαττα’ [thalatta, Attic dialect form for “sea”] or ‘θάλασσα’ [thalassa, non-Athenian form]?” Young Ronnie replied, in impeccably r-less English: “The latter.”

True story? No, probably not, but it’s at least ben trovato for the boy who would grow up to be dubbed “the wittiest young man in England.” In the star-studded firmament of Eton and Oxford before World War I, Ronald Knox’s light shone among the brightest. And while today his reputation rests on other works, he wrote some of the cleverest Greek and Latin verse that I’ve ever seen.

Figure 1. Knox ca. 1928.

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox was born in 1888, the youngest of six children. His father was an evangelical Anglican, Edmund Arbuthnott Knox, who would eventually become bishop of Manchester. His mother, Ellen Penelope (née French), died from influenza when he was just three years old. Some dark years followed for the family, but young Ronnie largely escaped the gloom, living for a time with a bachelor uncle, from whom he began learning Latin and Greek. “Began” perhaps understates the case: by the time he was six, he was reading Vergil in Latin and including bits of Greek in letters to his father.

At the age of eight, in 1896, Knox entered Summer Fields, a preparatory school near Oxford, where he stayed four years. Already he delighted in writing Latin verse: consider this product of his ten-year-old pen, the first of a series of stanzas in Alcaics addressed to one Florence James, who had paid a visit to his sisters:

Florens Jacobi cara sororibus

Fortuna qualis mobilis, hinc abis;

hic affuisti quinque soles

tempus et esse breve en videtur.

O Florence James to both my sisters dear

Like fickle fortune hence you go away

You here were present during five long days

And lo! the time doth seem to be right short.

The translation is Knox’s own.

The precocious boy placed first in the Eton scholarship examination of 1900, and entered Eton as a King’s Scholar that September. The next six years were a time of unbroken happiness and academic success. Knox was naturally gifted, and he’d already had the benefit of a sound grounding in Greek and Latin at that age when the mind is at its most receptive and the memory at its best. Despite being surrounded by other clever boys—even an average student at Eton back then could do things with Greek and Latin that professional classicists would marvel at today—Knox overtopped them all. He won prize after prize, was captain of the school, was elected to the exclusive Eton Society, published prose and poetry, and on and on and on. And his prowess in classical verse composition was already unmatched. For example, he had 25 sets of verses “sent up for good,” i.e. transcribed in fair copy to be preserved in perpetuity in Eton’s archives, an extraordinary achievement.

Indeed, even Knox’s greatest “failure” shows the extent of his powers: in 1904 he was runner-up for the Newcastle Scholarship, the highest prize at Eton, determined by a grueling multi-day examination in Classics and Divinity. In 1905, expected to win, he was again proxime accessit; the prize went instead to his friend and rival Patrick Shaw-Stewart. Finally, in 1906, all but certain to win, he came down with appendicitis and couldn’t sit the exam.

Knox had, however, already won the first scholarship to Balliol College—Patrick Shaw-Stewart won the third—and went up to Oxford in 1906. In addition to Shaw-Stewart, Knox was joined by other Eton friends, young men like George (“Hôj”) Fletcher, Julian Grenfell, Edward Horner, and Charles Lister. After the rigors of Eton, the Oxford classical curriculum held little challenge, and Knox explored a range of extracurricular interests while continuing to pile up prizes (the Hertford [1907], the Ireland [1908], and the Craven [1908]; the Gaisford Prize for Greek verse [1908] and the Chancellor’s Prize for Latin verse [1910]). He seems not to have prepared at all for his first set of examinations, in Classical Moderations, reasoning that he had read all the texts on the syllabus in his Eton days. This was a miscalculation. Although he could translate them into English, he was not equipped to supply the requisite commentary on textual variants and the like. He failed to achieve the first-class that he’d so confidently expected.

Reflecting a decade later, Knox wrote that “I only took a second in Mods; an incident to which I look back with regret, in so far as it must have been caused by my own unnecessary immersion in other ends, with satisfaction, because I do not suppose that, but for this disappointment, I should have worked properly for Greats, and with gratitude, because then as in other times of failure I experienced such generous sympathy from my friends.” Over the next two years he threw himself into preparation for Greats, especially into the study of Plato and Aristotle. He recounts, for example, that one of the best days of his life was one “on which, in a space of nine hours, I succeeded in reading the Republic from cover to cover”—in Greek! He duly concluded his undergraduate career in 1910 with a first-class degree in Greats.

Steeped in Christian piety from his earliest days, Knox had long contemplated entering into the family business, i.e. the Anglican ministry. And it so happened that a fellowship at Trinity College, Oxford, was then vacant, intended for a future chaplain. Knox was proposed and, even before he sat the Greats exams, elected. Thus in the fall of 1910 he moved from Balliol to Trinity and took up his fellowship, tutoring students for Honours Mods and preparing for his own ordination. But he would not be a churchman in his father’s mold: even at Eton, Knox had been moving away from evangelical Anglicanism and toward Anglo-Catholicism. He loved smells and bells and elaborate rituals; he went to High Mass on Sundays; he prayed in Latin. A High Church ritualist through and through, he was ordained an Anglican deacon in 1911 and priest in 1912.

At Trinity, Knox was scarcely older than his pupils, and he made friends of many of them, young men like Harold MacMillan and Guy Lawrence and Laurence Eyres (on whom see the further reading below). They bonded over Classics and Christianity, tea and repartee. This scene in Knox’s rooms, ca. 1911, is typical: Knox is sitting and looking out the window with his feet up, surrounded by young men. They’re perusing magazines. Suddenly, someone exclaims, “Here’s a good title—the Bishop-Elect of Vermont.” Knox swivels about and, before his feet hit the floor, declaims:

An Anglican curate in want

Of a second-hand portable font

Will exchange for the same

A photo (with frame)

Of the Bishop-Elect of Vermont!

Knox did have religious questions in these years, but no particular reason to doubt that he could and would find answers within the Church of England. He was a vigorous advocate for the Anglo-Catholic cause against more liberal strains of Anglicanism. And he clearly enjoyed his activity as a pamphleteering paladin; his Dryden-esque “Absolute and Abitofhell” gives the flavor of his satirical style. For Knox, the period 1910–14 was, in sum, an idyllic time, centered around friendship and spirituality and Oxford, with little thought spared for the outside world.

Figure 2. Knox (far right, smoking pipe) at a reading party in the Long Vacation of 1909. Reproduced by permission of Francesca Bugliani Knox.

In August of 1914, Knox had arranged for a reading party at an English country house, More Hall. A good stock of wine had been laid in, and spirits were high; a brilliant coterie of young men were to spend three weeks in convivial fellowship, staying up late into the night to debate questions philological and theological. Guy Lawrence wrote in anticipation, “I think we shall all have a priceless time.” The guns of August were to change all that. On August 4, 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. The undergraduates never made it to the reading party: within a week they had all volunteered for military service. Soon almost all of Knox’s Eton and Oxford friends had joined up. Knox’s cheery reading party turned into a solitary spiritual retreat.

When he returned to Oxford, Knox found it a ghost town and himself at loose ends. As a clergyman, he could not serve as a soldier; as an Anglo-Catholic, he felt he would be unwelcome among the anti-sacramentalist military chaplains. In desperation, he concocted a scheme to be surrendered into a prisoner-of-war camp, where he might minister to otherwise desolate devout Anglicans. The Foreign Office rejected this plan as collusion with the enemy. With ever-growing spiritual scruples, he was left to sit alone and read the names of his friends in the ever-growing casualty lists.

Hôj Fletcher was the first of Knox’s friends to die in the war, shot in the head by a sniper on March 20, 1915. Fletcher had been at Eton and Balliol with Knox; they’d shared digs. In 1911 he’d become a Classics master at Shrewsbury School; in 1913 he returned to Eton. When Fletcher died, Evelyn Southwell, another Shrewsbury Classics master, who had also been with Knox at Eton and Oxford but was two years his senior, felt called to take Fletcher’s place and so volunteered. Oxford was deserted and Shrewsbury was full of students and needed a Classics master. Cyril Alington, one of Knox’s old teachers at Eton, was Shrewbury’s headmaster. An arrangement was made: Knox took a leave of absence from Trinity and was seconded to Shrewsbury as a temporary schoolmaster, taking over Southwell’s Form V B in the summer term of 1915. He would work without pay, with the special provision that he would have weekends free to return to Oxford or London for religious services.

Figure 3. With Shrewsbury masters, from l. to r.: Rev. William Smith Ingrams (1853–1939); Hugh Edward Eliot Howson (1889–1933); Philip Bainbrigge (1890–1918); Knox.

Knox wrote that “I went to Shrewsbury as convinced as ever that my mission was to fight heresy and denounce compromise within the Communion of the Church of England.” Perhaps true, but within a few months, he was assailed by the gravest doubts, and he was on the point of converting to Roman Catholicism. After a single term, he wrote to Alington and suggested that he not return to Shrewsbury after the summer holiday. Alington replied that unless he’d actually become a Roman Catholic, he must return to Shrewsbury, and return he did.

Knox’s world was falling apart: his whole generation, including almost all of his closest personal friends, was being butchered. His soul was in spiritual torment. As he would write just a few years later: “All this time (August, 1915), while this turmoil of questionings was raging in my head, blow after blow was dealt me from without by tragic news of my best friends. Most of these had joined Kitchener’s First Army, the army of Hooge and of the Suvla landing. I could hardly read a paper or open a post without a fresh stab that threatened to shake my whole faith to its roots.” In successive strokes of doom he was losing his friends and his religion.

In this state of mental and spiritual anguish—“I . . . had just lost all the motive power which had hitherto directed my life,” he writes—Knox resolved to devote himself wholly to teaching and the life of the school. He kept his religious doubts to himself and projected an air of charming eccentricity and schoolboy bonhomie. And, as things fell apart, in his classical work he seems to have hit upon a center that could hold. In Classics and teaching, he found not just meaning and purpose, but joy. “On a day of full work I would be working from first lesson in the morning till midnight, or after midnight, with no interval except for meals and for reading my office, and every moment of it, except when my form showed signs of boredom in school, was unadulterated pleasure.” It was a time of crisis, but also a charmed time; he writes of the “immense happiness” that he derived from his duties, and he waxes poetic when recalling those days: “Sitting in the deep window-sill, while the evening mists began to rise from the adorable curve of the Severn that flows under the Schools, I watched [my pupils] wrestling with some intolerably eccentric piece of composition, in an indescribable atmosphere of electric light, crumpled paper, and chalk-dust, twenty independent lives not burdened with my knowledge, not troubled with my speculations, enough of human contact to preserve me from mere self-centredness or from the abandonment of despair.” It is to this brief period of spiritual ferment and didactic exultation that some of Knox’s best and most memorable classical compositions date.

We can still peer inside his classroom when we look at some of the papers preserved in the Shrewsbury Archives in a box labeled “Ronnie’s Papers and Games.” So, for example, he composed macaronic rhymes—rhymes at any rate when recited with contemporary English pronunciation—to help students remember the forms of Greek and Latin conditional sentences:

Figure 4. Conditional mnemonics from "Ronnie's Papers and Games."

ἢν μὴ εὐθὺς σιωπήσῃς

(If you do not stop those wheezes)

Ξενοφῶντα ἀπογράψεις

(Your unlucky ship will capsize).

Figure 5. More conditional mnemonics from "Ronnie's Papers and Games."

Ista nisi uox cessârit

(If that noise goes on—I bar it)

A te Naso transcribetur

(You’ll be writing Ovid later).

He guided his students to write elegiacs by preparing special English versions custom-made to slide into Latin verse. These came with topical relevance and self-deprecating humor and delighted him immensely:

Figure 6. Elegiac versification exercise from "Ronnie's Papers and Games."

[The student in Form V B speaks:] “Would-that (you), foul Germany, were-abiding by your sayings . . . (Then) I should not be-suffering endlessly (Phr.) so stupid a master . . . I complain that thou, thou art absent for me too long a time, who derivest a noble name from a South (adj.) well.” I leave the Latin elegiacs as an exercise to the reader.

This is schoolboy stuff, and yet we can trace how Knox brings his work at the chalkface to polished publication. Consider Hilaire Belloc’s poem “The Crocodile,” which begins:

Whatever our faults, we can always engage

That no fancy or fable shall sully our page,

So take note of what follows, I beg.

This creature so grand and august in its age,

In its youth is hatched out of an egg.

Knox rewrites for his pupils as follows:

Figure 7. Another elegiac versification exercise from "Ronnie's Papers and Games."

1&2 As-to-whatever (acc. of respect) we have sinned, there-is one-thing which we-may-boast; no fable sullies our books. 3&4 O! do not be unmindful that the monster, which, grown, terrifies with strength, is produced out-of an egg, and small.

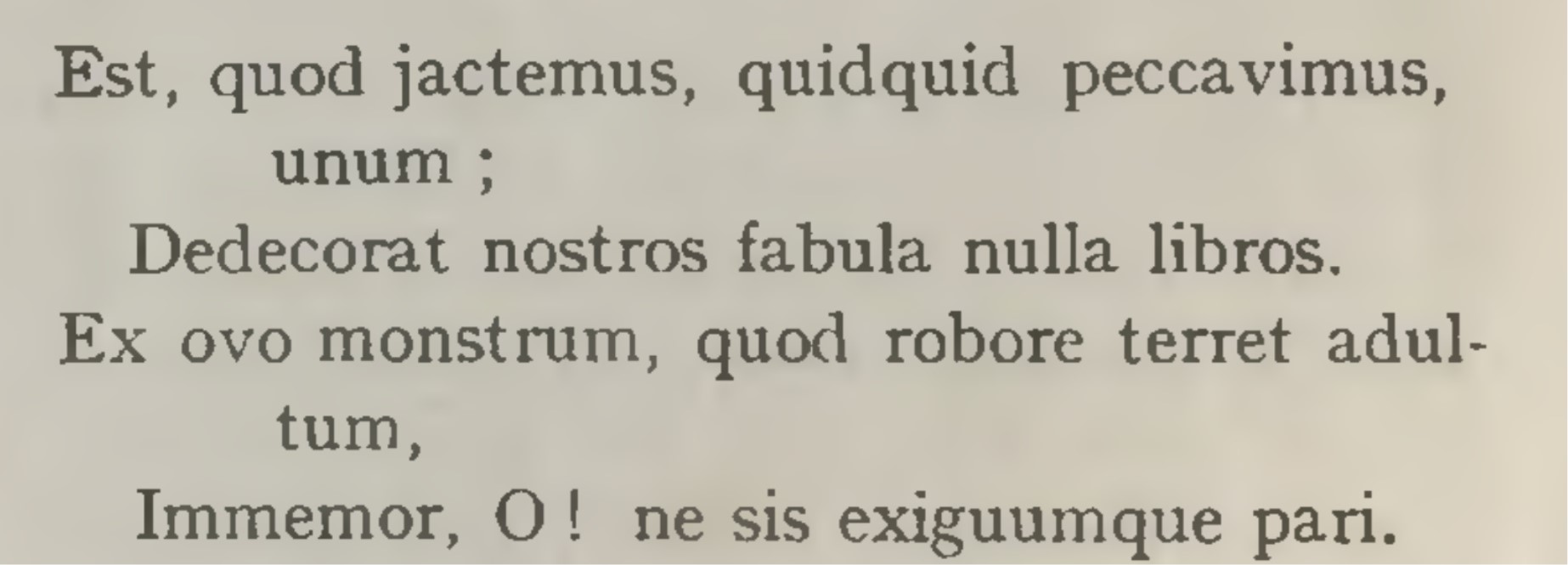

In November 1915, he published his version in The Salopian, the magazine of Shrewsbury School:

Figure 8. From The Salopian of Nov. 20, 1915.

Knox, of course, continues through the whole of the poem, as he does for a number of other of creatures in Belloc’s Bad Child’s Book of Beasts and More Beasts (For Worse Children).

Priceless individual lines can be found everywhere in Knox’s verses, and anyone who’s read them will have their own favorites. (Some of us have even felt moved to emulation: here’s my own attempt at updating one of Knox’s classic poems.) For example, I particularly enjoy this couplet from Lewis Caroll’s “The Jabberwocky”:

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

It becomes, via alchemical Knoxian transmutation:

ἔνθεν τε κἄνθεν διάτορον πληγὴν νέμων,

ἔσνιξεν, ἐξέσναξεν εὐκόπνῳ ξίφει.

Or take Knox’s “Telephoniazusae,” an iambic dialogue recounting a frustrating nineteen-teens telephone encounter between a man named Snoakes and a series of interlocutors. We pick up here mid-poem, in mid-conversation:

Τη. ὦ οὗτος οὗτος· Σν. πρὸς θεῶν, ὅστις περ εἶ,

ἄνω μολὼν τὸν Βίγγα κατακάλει δόμων.

Τη. (μυγμός.)

Σν. ἀλλ’ ἡδέως κλύοιμ’ ἂν, εἰ λάκοις μέγα.

Τη. ὡς οὐ παρόντος ταῦτ’ ἐρωτήσας μάθε.

Σν. πότερον θανόντος ἢ ’ποδημοῦντος λέγεις;

Τη. θάρρει, κάτεισι· κᾆτ’ ἀπαγγεῖλαι τί χρή;

Σν. ὁ Σνὼξ λέγων· Τη. Βλώξ; Σν. Σνὼξ μὲν οὖν. Τη. ὁ Σνωγμένων;

Σν. ΣΝΩΞ, Σνῶκα, Σνωκός, Σνωκί· σῖγμα νῦ—κλύεις;

My translation:

Telephone: Hello?

Snoakes: Dash it all, whoever you are, go up and get me Bing.

Te.: (Indistinct noise.)

Sn.: Could you speak up? I can’t hear you.

Te.: I’m afraid he’s not available.

Sn.: Do you mean he’s dead, or just not home?

Te.: Oh, he’ll be coming back. And what should I tell him then?

Sn.: Snoakes called and— Te.: Bloakes? Sn.: No, Snoakes. Te.: Nosnoakes?

Sn. SNOAKES: Snoaka (acc.), Snoakos (gen.), Snoaki (dat.): sigma, nu—are you listening?

The emotional antilabe kills me, as does the “Who’s On First?” routine with poor Snoakes (who feels moved to decline his own name to get his meaning across!). It seems that “can you hear me now?” has a very long pedigree.

Knox’s greatest talent lay in virtuosic parody. Consider this rendering of a school report into Latin elegiacs:

Name: C. Tibbles.

Form: V B.

Age: 16.6.

Average Age of Form: 15.11

Place: bracketed last.

Form Master.

Conduct. Late: leaves books behind: throws: whispers: eats: looks back on a friend, or out of the window: untidy, sulky, lazy, and something of a liar. Otherwise good.

Progress. Forgetful and backward: does not prepare his work, or attend in school: his written work is full of mistakes and untidily done. This explains his low place.

“Quid” tu quaeris “agit Gaius, mea cura, Tibullus?”

Altera pars quintae classis, ut ante, tenet.

Septimus huic decimus distat sex mensibus annus,

Vix sextum decimum plurima turba videt.

Si quo sit numero censendus forte requiris,

Inferior nemo, par tamen unus erat.

Cum sero venit, libris quoque saepe relictis,

Huc illuc iactat tela: susurrat: edit.

Respicit in comitem, vel, si vicina, fenestram:

Incomptus, tetricus, nec sine fraude piger.

His tamen exceptis—mites decet esse parentes—

Non est quod poenas commeruisse querar.

Immemor, ignarus, nec debita pensa peregit,

Nec quibus instituas vocibus aure bibit.

Res redit ad calamos: mendose scribere cernas,

Nec satis errores multa litura tegit.

Haec cum deficiant—non omnia possumus omnes—

Imum ne dubites obtinuisse locum.

Nor does Knox limit his wit to Greek and Latin. A particularly delightful sample of his English wit applied to a classical topic is provided by his “Particular Dialogue.” Form matches content at every turn, as each Greek particle’s contribution mirrors its meaning. The dialogue begins:

If you put your ear to the chink under the door of the Upper Sixth on the night before June the 21st, you can hear the Greek particles talking on the floor. Each of them must chip in once, and none more than once, for fear of being scratched out; so it is rather like a debating society. This is what I heard when I listened.

“Well, as I was saying,” began Mentoinun, “I don’t see any use in continuing to exist, when we make no real difference to the prose we live in.”

“Yes, but,” interposed Allaoun, “you must confess that we make some difference; the prose would be poorer without us.”

“Well, what about it?” said Timeen. “I don’t see the point of enriching, by our presence, these vulgar nouns and bloated verbs.”

“Be that as it may,” said Deoun, “I think in their heart of hearts they do recognize our value.”

[And the discussion continues, with more particles having their say.]

A glance at the wartime issues of The Salopian, where most of these jeux d’esprit were first published, shows the insanity of the contemporary circumstances. School cricket scores cheek by jowl with school casualty lists; obituaries lamenting brave young men cut down in the flower of their youth alongside witty acrostic puzzles in Latin. And while Knox was the author of those clever puzzles, he was assailed by grief too. Almost every single man mentioned in this article died in the war: Patrick Shaw-Stewart, Charles Lister, Julian Grenfell, George Fletcher, Edward Horner, Guy Lawrence, Evelyn Southwell. Laurence Eyres was assumed dead (he was unexpectedly restored to life in 1919, when he emerged from a Turkish POW camp). Knox’s whole circle of close friends first disappeared into the military, then disappeared forever. His world lay in ruins.

Knox resorted to classical verse not just to flee the realities of war and spiritual upheaval, but also as a way to grapple with his grief. In leafing through issues of The Salopian from late in the war, the reader is jolted by the following poem, from October 1918:

To P. G. Bainbrigge (“If I’m killed, I shall expect Greek elegiacs”)

καὶ γὰρ τίς σεο μᾶλλον ἐπάξιος; ὅντινα Μοῦσαι

κλαίουσιν τελετὰς εὖ μάλ’ ἐπιστάμενον.

θοῦρος Ἄρης, σὺ δὲ πολλὰ διδοὺς καὶ σκληρὰ μογῆσαι

σώματι, τὴν ψύχην οὐκ ἐδύνω κατέχειν·

ᾔδεε γάρ, Πάρνησσον ὁρῶν μάλα τήλοθ’ ἐόντα,

ζῶν σε καταφρονέειν· πῶς δέ, καταφθίμενος;

And who indeed could be more worthy of them than you? A man whom the Muses mourn, whose rites you knew full well. Impetuous Ares, you gave many hard labors for his body to endure, but you couldn’t claim his soul. While he was alive and gazed upon the peaks of Parnassus from afar, he knew how to despise you. What now that he is dead?

P. G. Bainbrigge had been another classical master at Shrewsbury, a colleague of Knox’s and a man of poetic tastes, who only joined up in 1917 after more Shrewsbury schoolmasters had been killed in action. He himself died in northern France on September 18, 1918, less than eight weeks before Armistice Day. And within a month of his death, Knox had written the requisite Greek elegiacs. He produced similar poems for Charles Lister and others. Such poems constitute a profound expression of grief. Beneath their occasional bluff façade, disguised under the cloak of a learned language, they allowed a man of the Edwardian age to express his emotions and reveal his true self in a way that he might not have felt comfortable doing in plain English. For men like Knox, writing Greek and Latin verse was a daily pastime; what might seem like a difficult and artificial exercise today was, for them, almost as natural as breathing. In a way, Knox was as much a wartime poet as Bainbrigge’s friend Wilfred Owen.

* * *

As 1916 drew to a close, Knox felt that he had to leave the “golden chains” of Shrewsbury. His religious scruples had become too much, and he had spent too long in keeping them at bay by his teaching. Moreover, Cyril Alington, the Shrewsbury headmaster, was decamping for Eton. Knox left Shrewsbury for good that Christmas, and began a new position in the War Office in London in January 1917. (He would read foreign newspapers for evidence of enemy propaganda.) That year he converted to Roman Catholicism. In 1918 he published A Spiritual Aeneid, an account of his journey to Rome, so to speak, peppered with tags from and allusions to Vergil’s epic. In 1919 he was ordained a priest of the Roman Catholic Church. He went on to a distinguished career as a priest and writer and speaker and translator of the Bible. But he never recaptured the ebullience of the pre-War years nor the manic creative activity of his time at Shrewsbury. Those lay buried with his friends.

When he left Shrewsbury, Knox didn’t completely leave behind Greek and Latin verse composition. In fact, for several years he continued to send occasional poems to The Salopian (such as the Bainbrigge elegy). And his memory would live on at Shrewsbury for decades. In 1941, for example, when he gave a speech at the school, The Salopian published an appreciative set of reminiscences (“one of the most brilliant of Classical Form Masters . . . who in the space of a single year built up for himself a legendary fame which still lives and perhaps grows among the anecdotards of Common Room”). But after Shrewsbury Knox’s life went in a different direction. In 1926, when he became chaplain to Catholic students at Oxford, he all but gave up classical versification. Nor were his verses collected and republished in his lifetime. Fortunately, shortly before he died, Knox gave his longtime friend Laurence Eyres permission to publish an anthology. In Three Tongues was issued in 1959. It is perhaps the wittiest and most delightful collection of Greek and Latin compositions ever put into print. While Knox’s reputation today rests on his hundreds of other books and articles (including not least his complete Englishing of the Bible), for me, In Three Tongues will always remain his monument and the truest testament to his exuberant genius.

Further reading

By Knox himself:

R. A. Knox, A Spiritual Aeneid (London, 1918): Knox’s spiritual autobiography, written shortly after his conversion to Roman Catholicism. The fundamental document for this period.

R. A. Knox (ed. L. Eyres), In Three Tongues (London, 1959): A posthumously published collection of some of Knox’s best classical compositions (and some other bits and bobs besides); edited by Laurence Eyres, Knox’s only close friend to survive World War I.

R. A. Knox, Signa Severa (Eton, 1906): Some published verses from Knox’s school days.

R. A. Knox, Juxta Salices (Oxford, 1910): Ditto from his undergraduate days.

R. A. Knox, Pippa Passes (Oxford, 1908): Knox’s Gaisford Prize for Greek verse.

R. A. Knox, Remigium Alarum (Oxford, 1910): Knox’s Chancellor’s Prize for Latin verse.

Knox wrote hundreds of other books and articles. Some of his best known publications are listed in his Wikipedia bibliography.

By others:

Sheridan Gilley, “Knox, Ronald Arbuthnott,” in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004): A reliable brief life.

Evelyn Waugh, Monsignor Ronald Knox (London, 1959): A biography written by a novelist: very readable, but Knox’s life is sometimes turned into a story, complete with romances and villains.

Penelope Fitzgerald, The Knox Brothers (London, 1977): A biography of Knox and his brothers (Edmund [“Evoe”]), Dillwyn, and Wilfred), written by Edmund’s daughter. First-hand memories. For classicists, at least as interesting as an account of Dillwyn, a papyrologist and code-breaker.

Francesca Bugliani Knox, Ronald Knox: A Man for All Seasons (Toronto, 2016): A volume of essays on many different aspects of Knox’s life, including World War I and Knox as a classicist. Fascinating discussions, and an excellent entrée into the archival material, some of which is included in the book. Also contains the only account I’ve seen of Laurence Eyres, who rendered many noble services to Knox’s memory.

Jennifer Ingleheart, Masculine Plural: Queer Classics, Sex, and Education (Oxford, 2018): On P. G. Bainbrigge; marvelous in its own right, with occasional sidelights on Knox.

Tom Keeline is Associate Professor of Classics at Washington University in St Louis. His book The Reception of Cicero in the Early Roman Empire was published by Cambridge University Press in 2018 and his edition of Cicero’s Pro Milone appeared in the Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics series in 2021. He is currently working on a new edition of Ovid’s Ibis. He also has a tendency to get interested in just about anything related to the ancient world and its reception, especially things related to Latin language and literature and the history of classical education and scholarship. Outside of Classics, he enjoys spending time with his family and reading novels.