Quentin Broughall looks at British public-school classical reception in The Salopian, 1860-1914.

Like most British public schools of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, Shrewsbury School placed classical study at the heart of its curriculum. Throughout the nineteenth century, a prominent array of classicists were educated at the school, such as Benjamin Hall Kennedy, author of the eponymous Latin Primer, who was also headmaster of Shrewsbury from 1836 to 1866. His students, H.A.J. Munro and J.E.B. Mayor, each became Kennedy Professor of Latin at the University of Cambridge. In addition, W.E. Heitland, the Cambridge don, and T.E. Page, the first editor of the Loeb Classical Library, also emerged from the school.

But, while these eminent examples demonstrate the high quality of classical teaching at Shrewsbury School, we have few sources on how schoolboys there appreciated classics on a day-to-day basis. Did pupils enjoy or merely endure the subject? Was their experience mere rote learning or did they find ways to be creative? On such questions most sources are silent. But school magazines are an excellent resource, whose pages reveal an extraordinary wealth of information about the contemporary schoolboy experience, especially regarding classical reception.

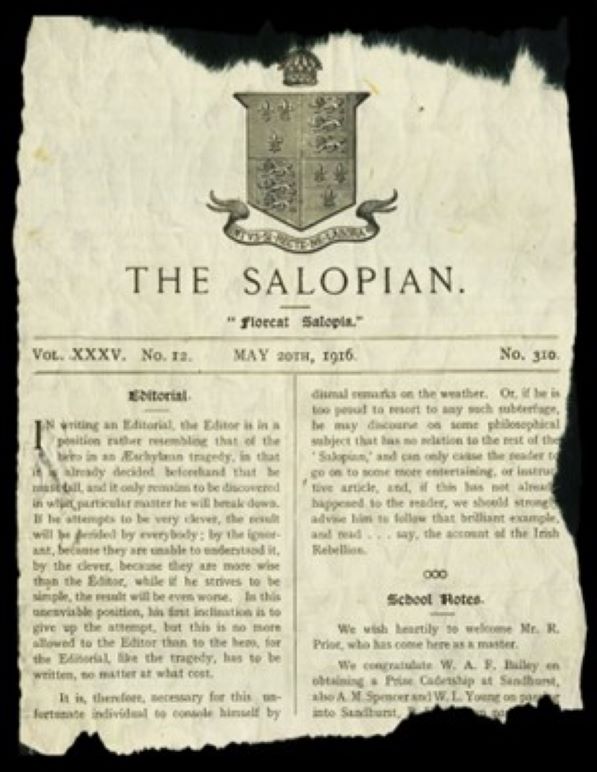

Usually written and edited by the pupils themselves under the supervision of a master, public-school magazines were designed to be consumed by the student body itself. As a result, they differ from other sources, whose readership was designed to be read by teachers or parents. Instead, school magazines present the public schoolboy speaking to his fellow students, with all of the adolescent in-jokes and immature wit one might expect. The school magazine at Shrewsbury was The Salopian, which made a halting start with the publication of a few issues in 1860, only to fall into abeyance until 1877. Revived in March of that year, The Salopian consisted primarily of articles on school news, debates and sports results, as well as current affairs and cultural matters.

But the saturation of student minds with ancient Greece and Rome is evident from the large number of classical references that dot articles on every subject. During the first three years of its publication, classical pseudonyms were commonplace in letters to the editor, including such soubriquets as Decanus, Nescio Quis, Servus, Zelotes Scholasticus, Digamma, Humanior, More Maiorum, Senex, Eudaimon, Auditor, Corvus Rudens, Quondam Socius, Mille Passum, and – my favourite – ‘Illegible Greek – ed.’. As with much else in the magazine, this shows the boys copying adults, since newspapers and periodicals of the day often featured correspondents writing to the editor under various nom de plumes, often derived from classical sources.

Classics and sports are also often found united in these pieces – complete with overwrought jokes and puns. For instance, an 1896 pastiche portrays a football match pitting ancient Greeks against Romans in teams manned with figures from mythology and history. When the two captains, Odysseus and Julius Caesar, toss the coin before the game, the wily Greek employs a double-sided coin; when caught, Caesar gives him a new one, which Odysseus attempts to pocket – compelling Caesar to ask him to ‘render unto Caesar…’. We also get diverse pieces such as ‘Fragment from the Crickets’, an Aristophanic cricketing pastiche; ‘A fragment from the works of Oppositesides’, about the illicit use of a part of the school grounds for games; and ‘Socrates on the Links’, where the philosopher reveals what a bad golfer he is.

Various parodies were published in The Salopian that endeavoured to put the literary techniques of the ancient epic to satirical ends. In April 1888, The Salopian announced ‘a new and entirely original rendering into English verse of [Virgil’s] great epic’ by ‘Professor Derry Down Derry’. The notice explained that ‘[t]he number of copies sold will be strictly limited to the number of sixpences paid on demand’ and that an ‘edition de luxe’ would follow ‘on hand-made paper (whatever that may be), embellished with authentic portraits of Aeneas, Dido, Achates and the Cyclops in photogravure (whatever that may be)’. This pastiche of contemporary classical translations even came complete with confected ‘opinions of the press’ from imaginary publications.

But the verse itself reduces the individual chapters of Virgil’s Aeneid to a series of rudimentary limericks. Its summary of Books I and II begins:

There once was a goddess whose eyes

Didn’t win in the show a first prize;

So she made a long speech,

And declared she’d soon teach

The Dardans her form to despise.

But she didn’t, and Pious old chappy

Lived to tell how his son, self and pappy

Fled the flames and the knife,

Though he lost his poor wife,

(Please remark th’ ambiguity happy).

So, while the framing of these pastiches was often sophisticated, their execution sometimes emphasises the adolescent authorship of these pieces. This can be again seen demonstrated in the conclusion of the adaption of Book XII of the Aeneid:

So the tale gets more gory and gory,

Which is all to the Pious One’s glory;

Till he finishes quite,

In a hand to hand fight,

Poor Turnus, and this stupid story.

Interestingly, there are very few pieces exclusively in Greek or Latin, despite the composition classes that would have dominated the classical curriculum. A rare example in Latin comes in 1910, with ‘Carmen Salopiense’, the first appearance of the school song, still in use today. On the following pages, however, is a piece entitled ‘Vergil at Shrewsbury’ which expounds upon the experience of school rowing with the magnified reference of sailing in the Aeneid. But it begins with the droll proviso that, ‘[f]or the benefit of our younger readers, we reproduce the English version only; the Latin can be had on application.’

Whenever ancient Greeks or Romans are portrayed in these pieces, there is often no difference registered between mythological and historical figures. This expresses the sense that, for the public schoolboy, classical antiquity represented a type of continuum where real and imagined planes blended in their classroom learning. A 1911 piece, ‘A Visit to Graecorombadopolis’, embodies this tendency. In it, a dreamer awakes in a modern city populated by the great and the good of antiquity, real and legendary alike. He decides to visit the theatre, finding Apollo conducting the orchestra and Orpheus playing first violin. When he reads the programme for the evening’s variety entertainment, he discovers: ‘1. Hector and Ajax, knock-about comedians. 2. Artemis with her troupe of performing dogs. 3. Witty and topical dialogues by Cicero and Demosthenes. 4. Quick changes by Perdiccas, who is acknowledged as the fastest changer known. 5. Weight-lifting and feats of strength by Herakles and the Titans. 6. Conjuring by Circe’.

But what started as a trickle of classical pieces in the early years of The Salopian quickened into a veritable flood from the turn of the century. Yet, the Edwardian era was a time when classical studies as a discipline was coming under increasing pressure to maintain its place in the curriculum and culture alike. Public schools were diversifying their curricula to include scientific subjects, while the continuance of the Oxford and Cambridge entrance requirement of compulsory Greek was debated vigorously throughout this period. Was the upward trend in classical pieces in The Salopian a conscious response on the part of the boys at Shrewsbury? Well, it’s hard to say. But there is no doubt that the pupils absorbed the Zeitgeist and responded to it in their own unique ways.

A satirical article from 1911 on the alleged decline of classical studies provides a fascinating glimpse of schoolboy views on the subject. The piece is divided between snapshots of Mr Pedagogue, a classics master, from 1861, when he is 23, to 1911, when he is 73. It opens with his dissatisfaction with his school form, which has only got halfway through Extracts from Latin Authors, when the previous form had almost completed it. In 1871, he chides his form that, when he first arrived at the school, ‘we were doing Caesar so easily that I thought of trying something harder. Now you boggle at simple stuff like these Extracts’. Twenty years later, he is upbraiding his pupils that, ‘when I first took this form thirty years ago it did Cicero and Thucydides. The bottom form was doing harder work than you. You find ordinary Caesar hard and think yourselves clever to read anything more than selections’.

But the joke derives from the fact that Pedagogue continues to believe that he had taught difficult authors, such as Aeschylus and Pindar, when he had only ever studied selections from ancient authors with the boys. Throughout, the speaker also directly connects national and imperial decline with deterioration in the quality of classical education. He expresses concern about the Russians and the Germans ‘beating us’, and England ‘becoming worn out’ and ‘dropping behind’. In addition, he makes reference to an increasingly-radical set of political figures whose views he threatens to become inclined to support. This begins with William Gladstone in 1871 and then moves to Henry Labouchère, John Burns, Keir Hardie and, finally, Lloyd George. Indeed, Pedagogue ends by insinuating that he might well be tempted to become a socialist. Other schoolboy authors, however, had a more positive view of the future of classical studies.

In a 1912 piece, ‘The School of the Future’, a German tourist, Herr Kidderwinke, visits Shrewsbury School in 2029, when it boasts over six thousand students and represents ‘the first school in the Empire’. He is shown the ‘Classical District’ of the school, visiting a ‘small Greek temple’, where ‘the Upper Forms learnt Greek’. In fact, the top five forms of the school speak nothing but ancient Greek. The piece cleverly depicts how classical texts have now been able to be reconstructed, explaining that, ‘in 1971, it had occurred to Professor Doblitzy that it would be possible to reconstruct a missing work of a classical author in the same way as a scientist reconstructs an antediluvian monster from half a jawbone, provided that a few lines were still extant of the lost masterpiece’. Through this method, the Polish professor had reconstructed ‘Livy’s missing books, the works of Ennius and a little Naevius’. His method, however, is soon exploited by a group who write ‘entirely original works, giving them the name of some famous poet or historian’ – which sounds a lot like artificial intelligence… Pointedly, Kidderwinke and his guide run out of time before they get to visit the Modern Side of the school.

Beyond the rote learning of the classroom, a rich classical culture is to be found flourishing in the Victorian and Edwardian school magazines of the British public school. Often irreverent, sometimes crude, the pieces in The Salopian showcase the intelligence, inventiveness and cultural awareness of its young authors. In the case of classical reception, they also demonstrate the ways in which public-school pupils expressed their interest in ancient Greece and Rome away from the sometimes-tedious pedagogy of the curriculum. In short, these classically-inspired parodies provided an opportunity for Shrewsbury’s pupils to rebel legitimately against the strictures of the school’s syllabus. What we find in the pages of The Salopian are certainly playful teenage kicks, but they also display a sophisticated, far-from-juvenile approach to the ancient world.

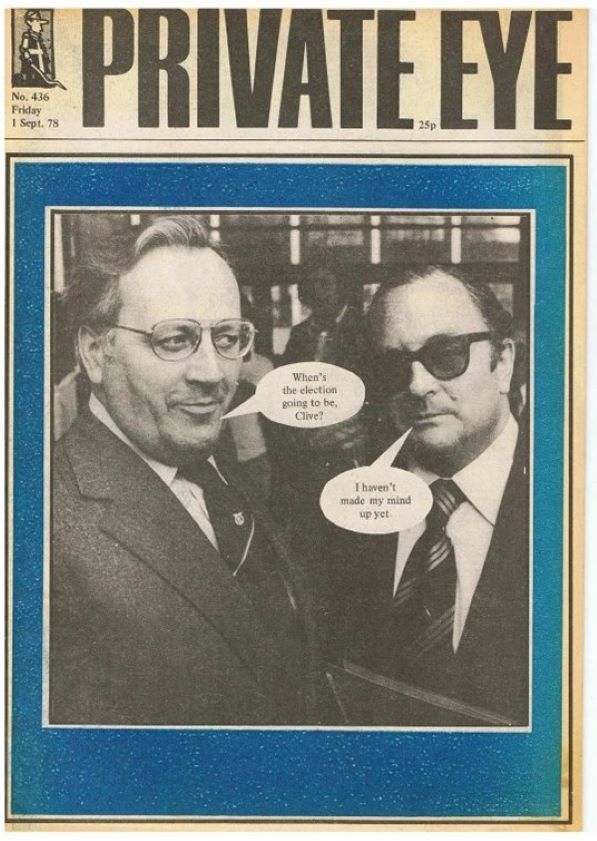

A half century later, in 1961, four students at Shrewsbury who once wrote for The Salopian, Richard Ingrams, Willie Rushton, Paul Foot and Christopher Booker, went on to found Private Eye, still Britain’s leading satirical publication.

So, one can partly trace to these rough-and-ready beginnings the evolution of the public-school and Oxbridge humour that defined the 1960s British ‘satire boom’ of Beyond the Fringe, That Was the Week That Was and Monty Python. The sophisticated cultural references, the surrealism, the stream-of-consciousness approach—it’s all there in miniature in the pages of the Victorian and Edwardian Salopian. Far from being a mere Shropshire fad, these schoolboy pieces were part of a wider trend in contemporary public-school culture, which also provide something of a missing link in the evolution of British humour from Punch to Private Eye.

Quentin Broughall is a classicist, scholar and writer from Ireland. A graduate of Maynooth University and Middlesex University, he holds a Ph.D. in Classics, as well as degrees in English, Modern History and Creative Writing. His book Gore Vidal and Antiquity was published by Routledge in 2022 and he is currently writing a novel.

DISCLAIMER: the views expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Classics for All.