Chris Whitton looks at the Agrippina plots

Dear friends,

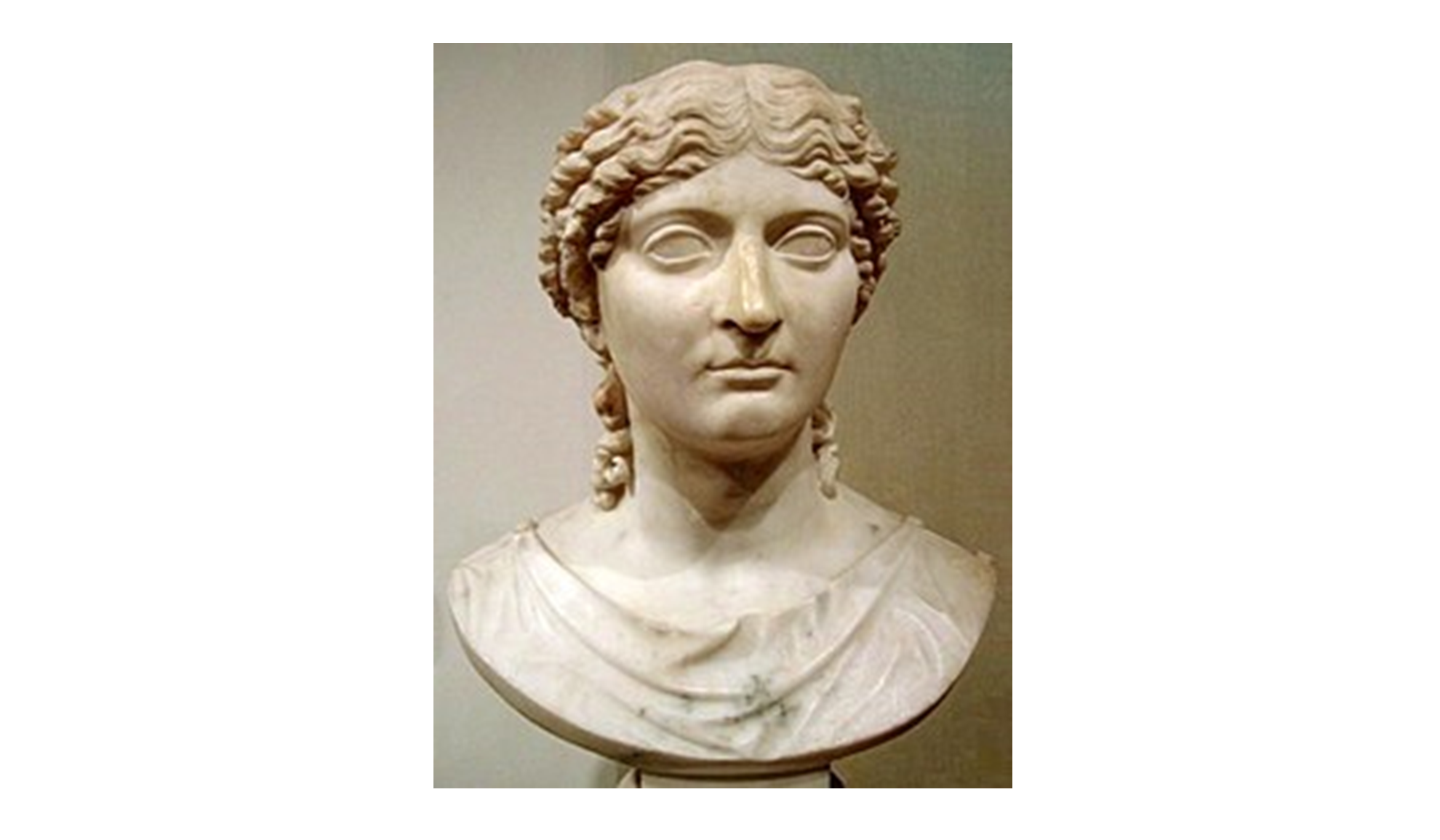

Nero’s murder of his mother is a low point in the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, and a high point in Tacitus’ account of it. These opening pages of Annals 14 bear reading and re-reading: Poppaea’s venomous whispering in Nero’s ear, the council of murder, the staged reconciliation dinner, the comic horror of the boat escapade, the intense psychological portraits of Agrippina and Nero in its wake, the brutal murder itself (‘Strike the womb!’), the aftermath, complete with quasi-obituary for Agrippina (‘Let him kill me,’ Agrippina had said, ‘provided he rule’) and mental torment for Nero, before his return to Rome as the parody of a triumphant general – all this (not to mention some hot material on Agrippina’s alleged attempts at incest with Nero) makes gripping stuff, but also responds superbly to close scrutiny. I’m sure many people have discovered that over the years, but I’ve been enjoying realising it for myself while inching towards a commentary on Book 14. One element that’s particularly caught my attention, in line (I must confess) with a hobby-horse of mine, is the role of self-imitation, or intratextuality, in Tacitus’ texture. For one thing, the death of Agrippina is a veritable symphony of echoes of earlier episodes in the Annals, and for that matter of the Histories. For another, it has some remarkable aftershocks in the rest of Annals 14, above all in the great British episode – Boudica’s rebellion – that straddles the middle of the book. Both of those webs of imitation have gone unseen by modern readers, at least, so I thought I’d use this little missive ad familiares to sketch out some of the outlines of these encounters and make a preliminary attempt at answering that great question: why?

Parallels, of course, are the stock in trade of ancient historians: whether we read Thucydides and Herodotus or Herodian and Cassius Dio, we keep finding their narratives, like history itself, repeating themselves: consider all those ‘types’ (monarch, adviser, wife …) and ‘schemas’ (the war council, the royal murder …). Tacitus provides a textbook example when he assimilates Nero’s accession (‘The first murder in the new principate …’, Annals 13.1) to Tiberius’ (‘The first crime of the new principate …’, Annals 1.6), establishing a large-scale artistic structure – the third hexad as a grim re-run of the first – but also inviting reflection on a historical parallel: the scheming wife (Livia/Agrippina) who poisons the old emperor (Augustus/Claudius) for the benefit of his stepson and her son (Tiberius/Nero). But there’s something special, I’m starting to suspect, about the death of Agrippina.

To start with the echoes of earlier episodes, it’s not particularly surprising to find Agrippina’s demise resonating with other recent departures from Tacitus’ stage: Nero’s first murder victim Britannicus in Book 13, Agrippina’s own victim Claudius in Book 12, and that other unforgettable wife of Claudius, Messalina, in Book 11. (Forgive me if I leave chapter and verse for another time: this is only supposed to be a letter, after all.) At further range, and more intriguingly, we find ourselves prompted to recall Tiberius’ final days (another tyrant whose public life ends with a hypocritical dinner party), and indeed the three imperial victims of our extant Histories: Vitellius, alone and afraid in the Palace; Otho, with his final volte-face into Stoic fortitude; but above all Galba. His murder might not seem an obvious analogue to Agrippina’s, but a similarity evidently struck Tacitus. There’s the death itself. Galba holds out his neck and tells the assassin to strike (Hist. 1.49); Agrippina thrusts out her belly and tells the assassins to strike (Ann. 14.8) – two different actions, but with an essential sameness of gesture. But Tacitus stitches several other elements of the Galba narrative into his Agrippina sequence (again you’ll have to take me on trust for now), as if to explore, and point up, some deeper likeness between Nero’s plot against his mother, that ultimate Julio-Claudian crime, and Otho’s plot against Galba, the crime that launches Tacitus’ Histories, and his historical career – a crime d’état balanced against a coup d’état, if you will.

Even more pervasive, though, is the ghost of Germanicus—and in interestingly complex ways. First, Agrippina is cast as another Germanicus. The boatwreck that nearly kills her curiously echoes the multiple shipwreck that nearly kills Germanicus (compare the confusion aboard in Ann. 2.23 and 14.5); Nero’s attempt on her life is paralleled with Piso’s alleged poisoning of Germanicus (‘So that was why she had been invited to dinner …’, 14.6 / ‘So that was why he had been sent to Syria …’ 2.82). At the same time, she replays her mother, Agrippina the Elder: her soggy arrival back at her villa on the Lucrine Lake, and the crowd scene that follows (14.6, 14.8), serially trace the great scene that opens Annals 3, as Agrippina arrives on Corfu, then at Brundisium, with Germanicus’ ashes. To complicate things further, Nero too is compared with Germanicus: ‘a night bright with stars’ (14.5) betrays the crime of his after-dinner boat trick, so like but also so unlike the way ‘a night bright with stars’ (1.50) helps Germanicus’ men mount a night-attack on some feasting Germans. Those are just a few of a whole string of echoes that permeates the scene, a thought-provoking bunch. One of those thoughts involves organic unity in literature: this responsion between the Tiberian and Neronian Annals, at least as elaborate as the famous one involving the accession narratives, attests to a positively Virgilian desire for structural cohesion, gluing together Tacitus’ maximum opus. Another involves family: it’s all too apt to find Germanicus’ shadow hanging over the murder of Agrippina (his daughter) by Nero (his grandson), the ultimate evisceration of his family line. And a third involves the sheer force of these echoes, which strikes me as exceptional even by Tacitus’ standards: confirmation in a new dimension of the weight he attaches – not just as dramatic author, but as historian and interpreter – to Nero’s killing of his mother.

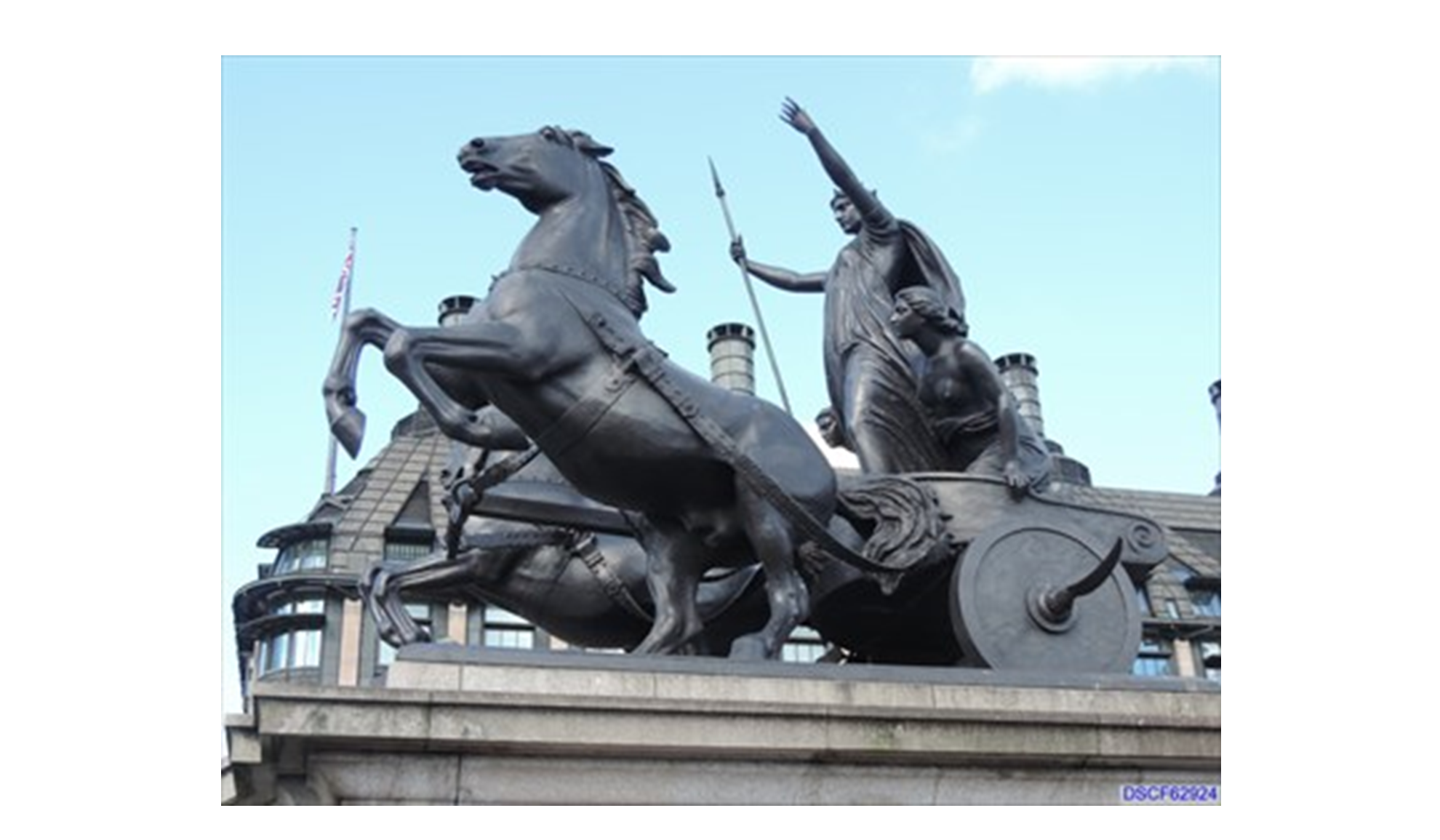

But I promised aftershocks too. I’ll spell out just one here, involving the other most celebrated part of Annals 14, the Boudica episode. Here too different parallels operate simultaneously, this time to the point of opposing each other. On the one hand, the British revolt against Rome and its empire is scripted as a re-run of Nero’s attack on Agrippina. Compare, for instance, Nero’s council of murder, mulling on the difficulty (‘and it seemed arduous …’) of poisoning Agrippina, a woman who had ‘fortified her body’ with antidotes (14.3), with the British rebels, pondering on the ease (‘and it did not seem arduous …’) of attacking Camulodunum, a town ‘ringed with no fortifications’ (14.31): two opposite scenarios set into dialogue by distinctive echoes. By the same token, the failure to sink the boat containing Agrippina (because ‘all were in confusion and the majority, unaware, were impeding even those who were part of the plot’, 14.5) is replayed and inverted in the success of the attack on Camulodunum (where the Romans were ‘impeded by those who, secretly party to the rebellion, were confusing their decisions’, 14.32). Such echoes invite us to join two quite different but related dots, from an absurd but murderous charade on the Bay of Naples, with a handful of lives at stake, to a revolt which cost three towns and 70,000 lives; is there even an implicit suggestion of (irrational) causation – rot at the heart of empire causing catastrophe at its borders?

At the same time, Boudicca herself is another Agrippina. That is a more obvious typological parallel, given their common status as empress figures; but Tacitus shows no compunction in letting it run in parallel, if I may put it like that, with the Britons as Nero. Curiously enough, it’s not so much Agrippina’s death that resonates here: it’s rather her rise in Annals 12. The comparison comes to a head in Boudicca’s celebrated battle speech. Carrying her daughters before her on her chariot, she opens (in good Roman style) with an elaborate proem: to be sure it was not uncustomary for the Britons to do battle under the leadership of women, but she stood before them not as a nobly born individual avenging a kingdom lost, but as an ordinary woman avenging wrongs done to her and her daughters (14.35). Now, back in Book 12 Tacitus devotes a paragraph to the parade of the conquered British king Caratacus in Rome. Caratacus addresses Claudius, pays homage to him, and then does the same to Agrippina, seated beside her husband on another dais. It is this last detail, not the splendid spectacle, that characteristically enough draws Tacitus’ attention, and a deadpan end to the episode: it was to be sure, he remarks, uncustomary for a woman to preside over Roman standards, but Agrippina presented it as her right: it was to her noble birth, she affirmed, that Claudius owed his reign (12.37). Delicate but serial echoes underpin an essential likeness of scene (Boudicca/Agrippina on high), and both sameness and disparity in their claims to nobility and leadership. What those echoes mean, as ever, is a more open question. We are surely invited to reflect on women in power, and it’s easy enough to pick up his slant when it comes to Agrippina, that ultimate threat to the patriarchy of empire; but his take on Boudica is harder to pin down. Is she too a transgressive figure? In some ways surely yes, another Cleopatra or Dido. But she must also – in this respect too like Cleopatra and Dido – be a figure of nobility, in her no-nonsense suicide, and as one of the long line of Tacitean opponents to empire.

At one level, the sorts of echoes that I’ve been tracing here are nothing special in the Annals, a match and more, as I’ve said, for the Aeneid when it comes to complex webs of self-referentiality. But I hazard that these are particularly dense webs even by his standards. In life, as in death, Agrippina evidently fascinated Tacitus, as much as she appalled him; and her murder, to repeat myself again, constitutes a nadir not just of her life but of the whole Julio-Claudian dynasty. Maybe that’s why his narration of it is subtended by especial depths of intertextual memory, and why it continues to resonate long after she has departed the mortal stage.

There are further twists to this tale, but life is short and this page is getting full, so I’ll leave it there: just a first, brief foray into untangling those webs, but I hope enough to entice you into joining me in picking up the Annals again (and again, and again …).

Chris Whitton is Professor of Latin Literature and Fellow and Director of Studies in Classics at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He has published a full commentary on Pliny the Younger, Epistles book II (Cambridge, 2013) and The arts of imitation in Latin prose: Pliny’s Epistles / Quintilian in brief, (Cambridge 2019). He is also co-editor of the forthcoming Cambridge Critical Guide to Latin Literature (Cambridge 2023).