Tony Woodman looks at how we know anything about the ancient world—and the importance of the languages.

There are two ways in which we in the twenty-first century can be in contact with the ancient Romans. One is archaeological: we can go to Rome or Pompeii or Hadrian’s Wall and we are able, touching the same stones that the Romans touched, or gazing at the same frescoes as those which diverted them, to be in physical contact with our distant ancestors. Of course even the most well preserved sites are badly ruined and far more has been lost than has survived. We can try to compensate for this loss by reconstruction, such as has been done at Vindolanda, that Northumbrian outpost; but no one pretends that a modern fortified gateway, however exact a replica, is the same as the one used daily by countless Romans two thousand years ago.

Our second means of contact is literary: we possess a vast number of Latin texts and, holding in our hands a speech of Cicero or an ode of Horace, we can find ourselves reading the same words as were read by these writers’ contemporaries. Of course even the best preserved works are corrupt, as is to be expected of texts which were copied and re-copied by hand across many centuries until the invention of printing. But with literature the situation is the converse of that which obtains with material remains. The extent to which the Aeneid is corrupt is relatively trivial and bears no comparison with the extent to which Pompeii is a ruined town: we may on a very few occasions be uncertain whether Virgil wrote this word or that word, but essentially we are reading the text as he composed it and as his contemporaries read it.

There is no third means of contact. We know a very great deal about the history of Rome, and it is that history which helps us to provide a framework for both ruins and texts, but history is an abstraction: we cannot re-live the murder of Julius Caesar in the same way as we can read Caesar’s account of his fighting in Gaul.

A Latin text is therefore an extremely precious commodity and, like all such commodities, it requires attention. What does this mean? I once had a colleague, a most distinguished historian of Greece and Rome, who believed that students would become better ancient historians if they read their primary sources in an English translation rather than in the original Latin (or Greek). He argued that, without the barrier of a foreign language to impede them, students would read much more extensively and as a result would increase their knowledge and improve their historical awareness. My colleague, who himself knew the ancient languages very well, took it for granted that a Penguin translation represented what the original author wrote. But Tacitus – to take an author in whom I am especially interested – did not write in English; he wrote in Latin, and it is a mistake to think that there can be a one-to-one correspondence between the two languages.

The accession of Tiberius will be acknowledged as an important moment in the history of the Roman empire. How does Tacitus describe it in the Annals? A key passage comes at 1.7.3, which is rendered as follows in the old Penguin translation of 1956:

For Tiberius made a habit of always allowing the consuls the initiative, as though the Republic still existed and he himself were uncertain whether to take charge or not. Even the edict with which he summoned the senate to its House was merely issued by virtue of the tribune’s power which he had received under Augustus.

Almost six decades later the new Penguin translation of 2012 says the same in different words:

For Tiberius began everything with the consuls, as if the old constitution was in force and he uncertain about ruling. Even his edict summoning the senate was issued under the heading of tribunician power, which he held under Augustus.

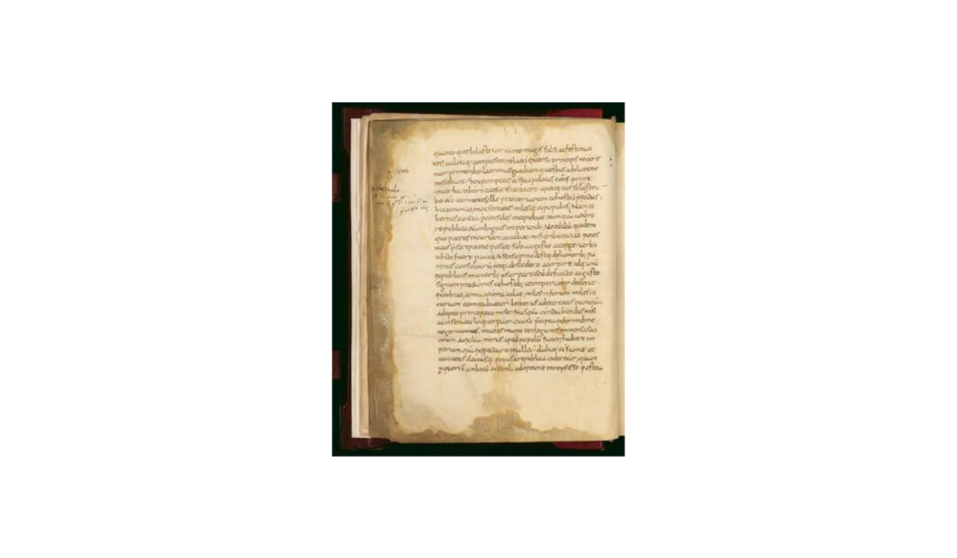

Both translations present us with a familiar picture: the hypocritical Tiberius, keen to give an impression of reluctance but in fact coveting power. Is this the picture with which Tacitus presents us? Here is the Latin as it appears in the single manuscript which has survived (I have filled out the scribal abbreviations but otherwise the text is as transmitted):

Nam tiberius cuncta per consules incipiebat; tamquam uetere re publica & ambiguus imperandi; Ne edictum quidem quo patres incuriam uocabat · nisi tribuniciae potestatis praescriptione posuit sub augusto acceptae.

To the Latinless this will simply be a meaningless sequence of unintelligible foreign words. Anyone with a knowledge of Latin, however, will see immediately that there is a problem. The words tamquam uetere re publica & ambiguus imperandi are separated off from the rest of the passage by semi-colons, as if they constituted a self-contained sentence, but there is no finite verb and the words do not make sense on their own. There is nothing surprising in this, since the punctuation is not that of the author (many scholars believe that the Romans did not punctuate their texts at all) but of some much later copyist: one therefore has to decide how the Latin should be re-punctuated in order that these matters should be rectified. Every editor known to me has omitted the first semi-colon (after incipiebat) and retained the second (after imperandi); and this is what our two translators have duly translated. But, if one semi-colon can be omitted, so can another: what if neither semi-colon is retained, and instead we punctuate after re publica? This changes the sense entirely:

And in fact Tiberius’ entire start was through the consuls, as though in the old republic; and, being ambivalent about ruling, even when he posted the edict by which he summoned the senators to the curia, he headed it only with the tribunician power received under Augustus.

No longer do we have the power-hungry hypocrite so beloved of our history books; in fact we have the exact opposite: an emperor who genuinely did not know whether he wanted to be emperor or not. This puts a quite different complexion on the start of Tiberius’ reign, which in turn stands a more than reasonable chance of opening up a reinterpretation of the reign as a whole.

The M manuscript of Tacitus Annales 1 for the passage under discussion

It would naturally be a considerable historical achievement if we were able to reinterpret the reign of so significant an emperor as Tiberius, but this example suggests that we do not stand a chance if we rely on English translations. Even if one does not accept the punctuation proposed here and prefers to retain that adopted in the translations, the fact remains that one is not even in a position to debate the respective merits of each – and hence the case of Tiberius in general – unless one has a knowledge of Latin. As I said earlier, we use ‘history’ to provide ourselves with a framework in which to understand texts, but it is clear that we need to be able to understand texts if we are to construct that framework in the first place. Knowledge of history and knowledge of Latin are interdependent.

It is said that some of those who nowadays teach ancient history in universities do not know any ancient language; but how can they teach a subject when they cannot understand the sources on which their subject depends? Nor is this question pertinent only to ancient history: can philosophers who teach Greek philosophy read Plato and Aristotle in the original? Or are they also dependent on the fortuity of a Penguin translation? The shelves of university libraries are laden with commentaries on ancient authors, each of them published in an effort at explaining their chosen text; classical scholars spend their professional lives submitting to learned journals detailed investigations of linguistic issues, sometimes the meaning of an individual word or usage. Some, perhaps many, of these scholarly contributions have the potential to affect our view of what the ancients wrote and hence of the world in which they lived, yet these works remain closed to those who rely only on English translations.

The problem extends beyond such practical areas as Greek philosophy or Roman history. When I was learning Latin, I seem to remember being taught that ago means ‘do’ or ‘drive’; but, if I now look up the Oxford Latin Dictionary, I see that the verb has forty-four principal meanings, many of them subdivided into three or more variations of usage. ago is one of the commonest verbs in Latin: it is used over seventy times by Horace, for example. Although on some of those occasions the meaning may well be ‘do’ or ‘drive’, it is a certainty that on other occasions some different meaning is in play: can we be certain that on each occasion an English translator has chosen correctly amongst the forty-four principal meanings? The likelihood seems small. And that is on the assumption that the Latin word has a single English equivalent, whereas it is almost guaranteed that the poet is packing as much meaning as possible into his deployment of the verb and that there is in fact no single equivalent in English.

David West spent much of the 1980s preparing a new Penguin translation of Virgil’s Aeneid. As he neared the end of the last book, he was faced by mentem laetata retorsit, the last three words of line 841, which led him to comment: ‘The Latin, like all Latin, is untranslatable.’ This from a scholar who had spent the best part of a decade producing almost 300 pages of English translation! Had he been wasting his time? It is a good question.

Tony Woodman was Professor of Latin at Leeds (1980-84) and Durham (1984-2004) before being appointed Basil L. Gildersleeve Professor of Classics at the University of Virginia (2004-17). He has published extensively on Tacitus, including The Cambridge Companion to Tacitus (2009), a collection of essays under the title Tacitus Reviewed (1998) and editions of Annals 3,4, 5 and 6 as well as the Agricola. His From Poetry to History: Selected Papers was published ten years ago; this year has seen the publication of his new edition of Horace Odes Book 3 (Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics) and The Cambridge Companion to Catullus.