Esther Eidinow goes back in time with the help of new technology.

You are in a tavern in a small town somewhere in Epiros in north-west Greece, in the second century BCE. A travelling mantis–– a seer ––comes round the tables offering oracles, healing, initiation into secret mysteries that will bring good fortune. He’s standing close to you, whispering intensely about his awesome powers, when the tavern’s owner overhears his pitch and tosses him out. The man standing next to you raises a cheer and then, in the way of tavern conversation, introduces himself, calls for more drinks and launches into a story.

The man’s name is Lysanias. A few years ago he and his woman, Annyla, were blessed with the birth of a child, a boy. Everything seemed to be going well, until he was visited by a disturbing dream. Not being one of these superstitious types, he could usually forget about such things, but this dream repeated itself a few nights later. Now, some people might go to the local wise woman, but he was afraid it might create gossip. So when a mantis came knocking on his door, he invited him in for a consultation . . .

The mantis told him that his dream almost certainly meant that the child was not his– and, for a very reasonable additional fee, he could concoct a curse against the man who’d done the wicked deed; perhaps throw in an amulet to keep his woman out of trouble; maybe brew up a potion, so that she’d have eyes for no one but him . . . Now, some people might have bought everything the mantis had to offer, but Lysanias had never had much use for that sort of thing. He bid the protesting mantis goodbye, and tried to forget what had happened. But a seed of doubt had been planted that kept growing. What if it was true that the child wasn’t his? Each day, his anxieties multiplied. He began to think that people were talking about him, laughing at him, behind his back. Maybe the mantis himself had spread the story, resentful that Lysanias had refused his wares. Finally, he felt he couldn’t bear it any longer. He told his household he was going to make a pilgrimage––he must attend the Naia festival ––and set off for Dodona. And when he reached the sanctuary, this is the question he put to the oracle: “Lysanias asks Zeus Naos and Dione whether the child Annyla bears is from him.”

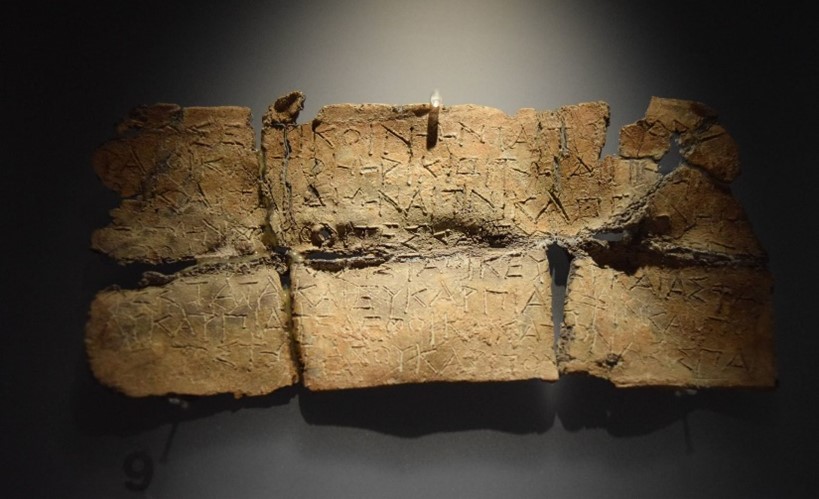

This brief, embarrassing attempt at fiction was my first attempt to honour the remarkable nature of the evidence found at the site of the oracle of Zeus at Dodona, Epirus in North-West Greece: thousands of tablets inscribed with questions—some with one question, some with more—not only by men, but also by women, and, even more remarkably, some of these men and women were enslaved. The story fragment opened Oracles, Curses, and Risk among the Ancient Greeks (2007), in which, alongside evidence for binding spells, I examined the question tablets that had been published up to that point, with a few further unpublished examples that Professor A. Ph. Christidis also very kindly shared with me.

Tablets from Dodona (neoskosmos.com)

Since then, the remarkable publication of Dakaris, S.I.; Vokotopoulou, J.; Christidis, A.Ph. (eds.) Ta chresteria elasmata tes Dodones ton anaskaphon D. Evangelide (Athens, 2013) has provided the texts of thousands more of these tablets: some are so fragmentary, we cannot work out their meaning; others tantalise us with longer texts—like the one above—which offer tiny glimpses of the vicissitudes of myriad, ancient lives. This material is a remarkable gift from the past, offering us insights into the day-to-day concerns of ‘ordinary’ people, a constituency that we seldom hear from directly in the ancient evidence. We can imagine them, as they gathered at Dodona to ask their questions of Zeus, who was thought to be somehow present in the oracular oak tree that was the focus of the sanctuary …

My initial study of Dodona focused on the risks that prompted those men and women to visit the sanctuary and write tablets. I took the term ‘risk’ in a socially constructed sense: that is, I approached it not as an ‘objective’ quantity, but in terms of the sense of potential danger that individuals and communities develop according to their cultural nexus of values and beliefs. Notions of authority, responsibility, explanations of misfortune and allocations of blame—these shape and are shaped by cultural perceptions of risk. The anthropologist Mary Douglas who developed this theory illustrated her approach by referring to the Lele of Zaire. As she describes it, in Risk and Culture (co-authored with Wildavsky, 1982) the Lele, subject to ‘all the usual devastating tropical ills’, focus on the risks of being struck by lightning, barrenness, and bronchitis. I used this theory to explore the question of which areas of life seemed so worrying to the ancients that they would bring their anxieties to the gods—I also looked at cursing in this light—and to investigate what it was about those areas of life that created a sense of danger.

In general, such an individualised approach, to risk or to oracles, was and remains unusual: the discipline of ancient Greek history tends, quite understandably, to focus on oracular consultation as a community or group event. Research in this area largely concentrates on explaining oracular consultation in functionalist terms, primarily concerned with revealing how and why—in a relatively sophisticated culture—such an apparently irrational activity should prove so popular.

Thinking about the individual in the divinatory context, and attempting to explore the nature of their experience, challenges that paradigm. But things are changing: in 2016, Lindsay Driediger-Murphy (Calgary) and I ran a conference on Ancient Divination and Experience, which resulted in a published, open access set of essays (OUP, 2018) that explore this question of experience in greater detail. Our concern was not so much the ‘religious experience’ of individuals; instead, our contributors set out to examine the evidence for the cognitive states of those engaged with such activities—the beliefs, the hopes, the anxieties of consultants. When we begin to understand these very human experiences, we reasoned, we begin to be able to better understand the role of human beings in the divinatory process—and the perceived structuring of relationships between human and divine.

This is some of the theory; but the personal stories of those individuals who wrote the questions at Dodona still tug at the imagination…. Is it possible to evoke their experiences? What would it be like to visit the oracle at Dodona?

In 2017, I teamed up with Kirsten Cater, Professor in Computer Science; Senior Lecturer in Film and Television and director and producer, Dr. Jimmy Hay; Orange Vision Productions (https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/en/persons/jimmy-hay) and a wonderful group of Bristol students to begin to evoke that experience. Funded by the Leverhulme Trust, we created ‘Visiting the Oracle: an Immersive Experience’: a series of 360-degree films that depicted historical oracular consultations at the ancient oracle of Dodona: these stories were based on historical questions, and the site was conjured by an extraordinary oak tree in Ashton Court, Bristol. If played in 360-degrees (guidance on the website) the viewer finds herself there in the experience, standing in the Bristol sunshine. The videos have been viewed by thousands of people, and we have had some terrific feedback, suggesting that users have found this an inspiring and thought-provoking experience.

It became the prototype for the next stage…

The Virtual Reality Oracle project (VRO), funded by the AHRC (2020-23), aims to recreate an approximation of the experience of consulting the ancient Greek oracle of Zeus at Dodona, using VR. Unlike many recent ventures in VR that focus on the ancient world, this project is not primarily concerned with recreating the topography and architecture of the site. The VR experience visits Dodona in the mid-fifth century BCE (the site did not feature a stone temple until the fourth century BCE and the grander buildings—the treasuries and the theatre, for example—whose ruins can be seen now, were built much later). The VRO focuses on the stories of people who may have visited the oracle, seeking to evoke the diversity of the ancient world; aiming to address questions of subjective historical experience by creating a convincing reality for a modern visitor to that ancient site.

The research team, from Bristol, Bath and KCL, is multidisciplinary: we comprise ancient historians, human-computer interaction specialists, psychologists and neuroscientists. We are hoping to use the VRO to learn more about the ancient world—a deeper understanding of the experiences of individuals and the complex operations of a significant site and the ritual practices that took place there; new perspectives on ancient religion and ancient Greek culture. We hope to gain insights into the uses and effects of VR—the design and development of immersive experiences of historical contexts; some sense of the sensory responses to and potential brain processes engaged by this experience. Will such an experience enhance modern audiences’ understanding of, and empathy with, historical subjects? What could it mean for the use of VR in educational settings, for museums or cultural heritage contexts?

We hope to be able to contribute to the answers to those questions. Our project team also includes school-teachers and curators, who are working with us to ensure that the VRO will support their teaching. As most of the readers of this column surely know, Dodona appears on the A Level OCR syllabus for Classical Civilisation: under the Key Topic ‘Personal Experience of the Divine,’ it lists ‘The oracle at Dodona, including: the nature of the help and advice sought from the oracle by private individuals.’ In the second half of the project, we are planning to bring the VRO to museums and classrooms—and we hope that we will bring some sense of the personal experience of ancient individuals to those modern settings.

Professor Esther Eidinow holds the chair in Ancient History at the University of Bristol. Her publications include Luck, Fate and Fortune (I.B. Tauris 2011) Oracles, Curses and Risk among the Ancient Greeks (Oxford University Press 2007) and Envy, Poison and Death: Women on Trial in Classical Athens (Oxford University Press 2016). She is leading the AHRC-funded VRO project (2020-2023) and welcomes enquiries about it. Do get in touch with her: [email protected].