Christopher Gill looks at how the ancient Stoics can help us in our modern lives

A prominent feature of modern life is widespread interest in Stoicism as a source of guidance for living. There are numerous recent ‘life-guidance’ books based on Stoic principles, as well as on-line courses offered by organisations such as Modern Stoicism (https://modernstoicism.com) and the Aurelius Foundation (https://aureliusfoundation.com), both of which I am involved in. Why the interest?

In broad terms, it is not difficult to see why many people are looking for a framework for living today. The waning force of traditional sources of ethical guidance, such as churches, the family, local communities, and political parties, have left a gap which writers on life-guidance, often based on some version of Buddhism or Mindfulness, have tried to fill. But what has given Stoicism special appeal for this purpose?

From Socrates onwards, Greek philosophers aimed to provide not just ethical theories but a basis for living, sometimes presented as a craft or expertise in living. In the case of Stoicism, writings such as the discourses of Epictetus, Seneca’s Letters, and Marcus Aurelius’ philosophical diary (the Meditations) offer eloquent statements of core Stoic principles. Several recent translations of these works, with introductions and notes, have served as widely selling points of access to Stoic ethical guidance.

Also crucial has been the fact that these texts have provided material for devising exercises to embed Stoic attitudes in daily practice and emotional patterns, such as those used in the Modern Stoicism ‘Stoic Week’. A much-used exercise (based on Epictetus) is the ‘dichotomy of control’, distinguishing between what is and is not within our control as agents, and focusing on what we can control, rather than what we cannot. This simple exercise has wide-ranging implications for forming our objectives in life and for managing emotions.

A second exercise (provided by Hierocles, a late Stoic) is directed at modifying our patterns of personal relationship and concern. Hierocles invites us to see ourselves as placed at the centre of a series of concentric circles, ranging from our immediate family, through more distant relationships, those of neighbourhood or country, to humanity in general. He advocates that we work towards contracting the circles (one circle at a time), for instance by calling our more distant relatives ‘father’ or ‘sister’. The overall aim is to extend the scope of our concern for other people, concluding in the recognition of all human beings as members of a single community. A third exercise (based on Marcus Aurelius) consists in the adoption of a ‘view from above’, in which we try to picture our own situation from a cosmic standpoint. The aim is to place our immediate (seemingly urgent) preoccupations in a wider perspective of space and time. Questionnaire responses to the courses incorporating these exercises consistently suggest that they have a positive impact on people’s sense of wellbeing and flourishing and emotional balance.

What are the Stoic philosophical ideas which underpin these exercises and make it worthwhile to deploy them as part of a programme for reflective living? Here are four key ideas. One is that happiness does not depend on factors such as prosperity, wealth, success, fame, or even the wellbeing of our family and friends, though such things have a positive value. Happiness depends on exercising our own agency to develop the virtues, specifically the four cardinal virtues (wisdom, courage, justice and temperance or self-control), which cover the main areas of human experience. This ethical principle underpins Epictetus’ advice to focus on what lies within our control (that is, developing the virtues and happiness based on virtue), rather than on things such as prosperity and fame, which fall outside our control.

A second idea, closely linked with the first, is that human beings have an in-built capacity for ethical development. Ethical development takes its starting point from two primary instincts common to human beings and other animals, to care for ourselves and to care for others of our kind, combined with the distinctive human capacity for using reason to shape our motives, responses, and actions. In human beings, care for ourselves, if fully developed in a rational way, leads us to gain and exercise virtue and also to recognize the distinction in value between virtue and other things such as wealth and fame. Care for others, if developed rationally, leads naturally both to parental love (a motive shared with other animals) and engagement in communal life more generally. A further aspect of ethical development is the recognition that all human beings form a broad community, as rational and sociable animals. This second strand of development underpins the exercise of Hierocles on contracting our circles of relationship and expresses the human capacity for progressive expansion of our ethical engagement and concern.

The Stoics also maintain that, in adult human beings, emotions and desires are shaped by beliefs and reasoning. Hence, ethical development does not only affect our understanding of what is really valuable and the nature and scope of our concern for others, it also transforms the pattern of our emotions and desires. In place of misguided and intense emotions or ‘passions’, we experience what the Stoics call ‘good emotions’, based on sound judgements and marked by calm and consistent reactive attitudes. The positive results of the Stoic week questionnaires bear out the idea that Stoic principles and practice can have a beneficial effect on our emotional state.

The Stoics also believe that these ideas about virtue and happiness, and about ethical and emotional development, are not simply matters of theory (or wish-fulfilment) but are, in various ways, grounded in nature. These ideas are seen as reflecting the distinctive character of human beings as rational and sociable, when compared with other animals. They also express the fact that human beings form an integral part of the natural world, and that the natural world embodies principles such as benevolent care and order or coherence which are also central for human ethics. This point underlies the Stoic definition of happiness as ‘the life according to nature’ (meaning both human and universal nature). It also underpins the exercise based on Marcus Aurelius, which suggests that adopting a cosmic perspective, which abstracts from our localised personal concerns, can make a positive contribution to ethical life, by linking us with nature as a whole.

These Stoic ideas are not only significant for modern concerns because they underpin courses and exercises which have proved useful as life-guidance. They also form part of an ethical theory which is substantial and valuable in its own right, and which is as coherent and credible as that of Aristotle, for instance. Also, certain features of Stoic ethical theory enable it to make a distinctive contribution to modern philosophical debate. These points are explored in my recent book, Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance (Oxford, 2022). Hence, we can give a second answer to the question posed here, ‘Why Stoicism Today?’, by considering certain ways in which Stoic ethical ideas intersect with, and can inform, modern theoretical concerns.

For one thing, as others too have stressed, the Stoic idea that emotions and desires are based on beliefs and reasoning anticipates the modern cognitive view of emotions. This point of connection is important for some modern psychotherapists who have taken Stoic ideas and practice (especially in Epictetus) as a model for cognitive methods of therapy. These connections between Stoicism and cognitive therapy have informed the on-line courses offered by Modern Stoicism.

Another notable feature of modern moral philosophy is the revival of the kind of ethical theory common in ancient thought, centred on the concepts of virtue and happiness. This represents an alternative to more standard types of modern moral theory based on notions of duty or human benefit. Contemporary virtue ethics has, typically, taken Aristotle as its ancient exemplar and source of inspiration. However, I argue in my book that Stoic theory is, in various ways, more suitable for this role.

First, Stoic thinking on the relationship between virtue and happiness is more coherent and fully worked-out than Aristotle’s. Also, the ethical rigour of the Stoic conviction that happiness depends solely on virtue, as distinct from other things generally regarded as good, matches at least some modern expectations of what is required for a moral theory. The Stoic account of ethical development gives a more central role than Aristotle does to other-benefiting motives and actions and, in this respect, their theory chimes well with contemporary moral thinking. The emphasis on benefiting others, in principle, any given human being is evident, for instance, in Hierocles’ exercise on expanding the scope of our concerns.

A further striking feature of Stoic theory, noted earlier, is the close linkage between ethical ideas and the concept of nature, both in the sense of human nature and the natural world more generally. This marks a point of contact between Stoicism and the more naturalistic versions of modern virtue ethics put forward by contemporary thinkers such as Philippa Foot and Rosalind Hursthouse.

Further, the fact that Stoicism connects ethical theory not only with human nature but also the natural world as a whole has taken on new interest in the light of modern environmental concerns. The Stoic worldview stresses ideas such as internal coherence, order, and a stable basis for natural growth and reproduction. In the light of the Stoic worldview, global warming and climate change present themselves, with renewed force, as disruptions of the natural order and ones we have powerful reasons to counteract as much as we can. The Stoic definition of happiness as ‘the life according to nature’, meaning, in part, nature as a whole, is also suggestive for this purpose. Given the environmental situation in which we now find ourselves, our concepts of virtue and happiness need to take account of the way our actions bear on nature as a whole as well as on ourselves and other human beings.

For these and other reasons, I think that Stoic ethics speaks powerfully to us today as well as providing a valuable basis for life-guidance.

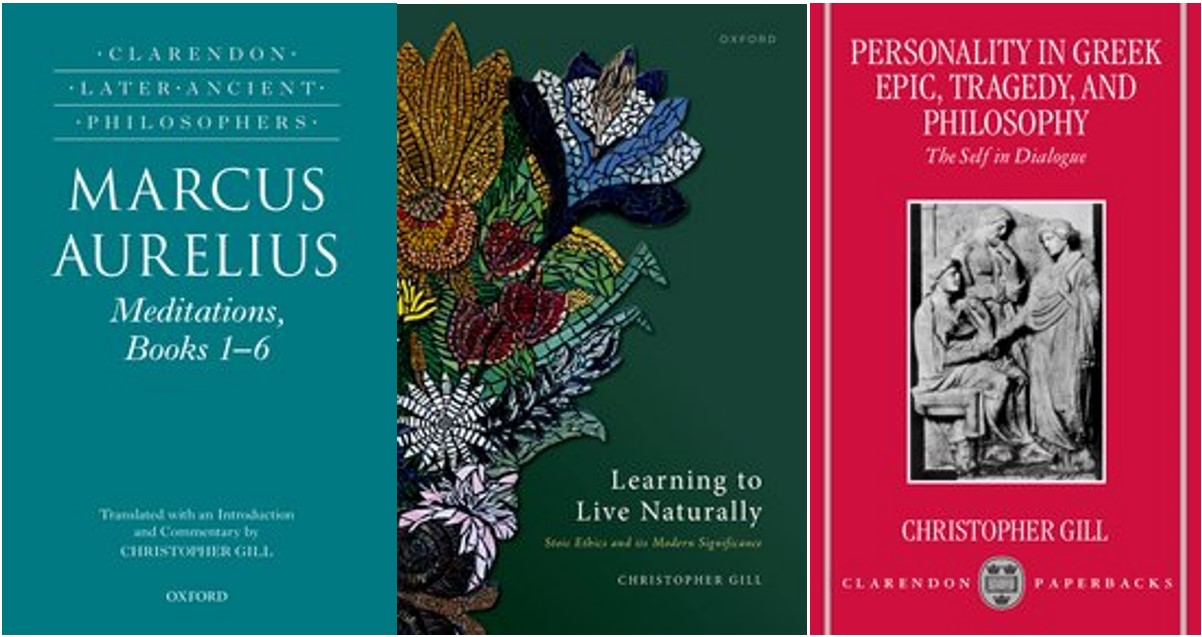

Christopher Gill is Emeritus Professor of Ancient Thought at the University of Exeter. He has published widely on Ancient Philosophy and literature and his books include: Personality in Greek Epic, Tragedy, and Philosophy: The Self in Dialogue (Oxford 1998), his translation and commentary on Marcus Aurelius Meditations Books 1-6 (Oxford 2013). His book Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance was published by Oxford in 2022.

DISCLAIMER: the views expressed in these articles are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Classics for All.