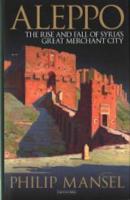

I.B. Tauris (2016) h/b 250pp £17.99 (978178453 4615)

M.’s book mourns the destruction of a remarkable and admirable city, bringing its history as up to date as possible (May 2015). It is, however, not really a book that belongs in the sphere of ancient history. After three pages of introduction, taking the history of Aleppo from 2250 BC to the Ottoman conquest of 1516, the main body of the book begins, covering Aleppo as an Ottoman city to the present day. Part 1 (65 pages) outlines this history in twelve brief chapters, Part 2 (140 pages) provides primary sources, accounts by Europeans who visited Aleppo from the late 17th to the early 20th century.

M. explains how and why Aleppo flourished under the Ottomans, who themselves flourished because of their more outward-looking attitude (compared for example with the Seljuk Turks). Appreciating their need for foreign allies, they encouraged contact with other nations such as France and valued a mixed society within their empire. Christians, Jews and Armenians could run their affairs under the ‘light hand’ of their Ottoman rulers. Though an Arab city, Aleppo was governed by Turks, and the rule of governor with his ‘divan’ or council provided reasonably equitable government.

Aleppo’s function as a major trade emporium, boosted by the opening up of Iskenderum as the nearest port, brought prosperity to the city and encouraged foreigners to settle there. Armenians controlled the silk routes, Venetian merchants brought their ‘lingua franca’, Arab horses were exported to Britain. Many consuls were stationed there to support their countrymen in their business affairs. Entertainment and culture thrived: all nationalities used the hammams (men in the morning, women in the afternoon); both Arab and Christian scholars studied Arabic literature and grammar; architecture flourished, fine houses were built, some of which survived until the current civil war—M. describes the Beit Gazaleh with its six courtyards and ‘wooden panels from 1691 (now stolen)’.

Even in its long years of prosperity, Aleppo saw episodes of sectarian intolerance, but these were comparatively few for the time. However, they began to increase during its years of decline in the early 19th century. Violence between Muslim and Christian in 1850 was the worst until the present day. As the Ottoman empire was assailed by reforming forces and military defeats in the early 20th century, foreign powers intervened more and more. The French mandate was unpopular with Muslims, popular with Christians; indeed such was the instability of the surrounding regions that Aleppo became a ‘Noah’s Ark for Christians’, receiving Armenian, Assyrian, Syriac and Orthodox refugees to remain ‘distinctively multi-denominational’ in 1930.

Independence subordinated Aleppo to Damascus, for the first time in its history. Relations between the two cities had often been strained, and the government’s extreme response following the murder of 30 Alawite military cadets set the tone for the current troubles. Nevertheless Aleppo prospered for several years under the Assads until shockwaves from the Arab Spring returned the city to ‘a horrific re-enactment of the wars which before 1750 had raged between Iran and the Ottoman Empire.’

Part 1 is fully referenced, clear and succinct. Part 2 ‘Through Travellers’ Eyes’ gives full and lengthy accounts of visits to the region by travellers from 1693 to Gertrude Bell and Leonard Woolley in the early 20th century. Frustratingly this section is not annotated at all; the earlier documents would benefit greatly from explanation of some of the terms: ‘… costly stones, by the Arabians called Bazaer… The Persians take from these a peculiar sort of bucks, and use the powder against mortal and poisonous distempers.’ Nevertheless it is interesting to read the later accounts, where archaeologists and spies rubbed shoulders in the region. Another failing is the paucity of maps. Only two are provided, both of which are most inadequate. Given the frequent discussion of Aleppo within its surrounding region, a proper complement of maps would have been most helpful.

These complaints apart, this is an interesting and engaging book, recommended for those wanting a deeper understanding of the current situation in the area.

Hilary Walters