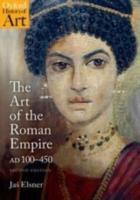

OUP (2nd edn., 2018) p/b 314pp £19.99 (ISBN 9780198768630)

E., in the 20 years since the publication of the first edition of this text, has established himself as one of the most insightful interpreters of ‘visuality’ in the ancient world. The period which the book treats is one of profound change in the Roman world: developments in the imperial system, the shift of power away from Rome itself, and (of course) the rise of Christianity and the decline of polytheism. E. reacts against a narrative of decline from the idealised ‘classical’: rather than seeing the rise of Christian art as a rupture with the pagan past, he shows a gradual process of adaptation and natural development. Indeed, there are remarkable continuities despite (and sometimes, precisely because of and in reaction to) great social and political upheaval. The book, therefore, is less about the technical development of art over the period, and more an exploration of the visual in cultural history.

The synchronic arrangement of the book allows these parallels and continuities to be seen more clearly. To pick a few particularly striking examples: a fifth-century ivory panel depicting the translation of the relics of St Stephen echoes a third-century triumphal arch carving of the emperor Galerius’ adventus into Salonica; both of them are remarkably similar to Herodian’s description of Elagabalus’ triumphant procession of the god Baal into Rome. Despite differences in religion and context, this kind of public spectacle (with remarkably stable visual tropes) clearly remains a constant feature throughout the period. Representations of these processions (especially on public monuments) reinforce their symbolism and social function, and in turn, later processions are deliberately designed to echo existed imagery of former, similar processions, in a bid to claim authority and continuity.

Perhaps even more interesting, a gilded plate from Iran (5th-7th century AD), showing a female deity drawn on a chariot, is quite clearly a copy of a second or third century gilded silver plate, also from Iran. The earlier version, however, depicts a male deity, combining classical iconographic schemes of Dionysus and Hercules. The readiness with which Greek religious art is incorporated into a Sassanid domestic context, and then refigured for a later audience, shows the flexibility with which both craftsmen and audience were able to reimagine old material for new circumstances. This latter example comes from a new chapter (‘The Eurasian Context’) written for this second edition, which maps the interconnectedness of cultures from Western Europe all the way to China and India. It is one of the clearest and most concise introductions to this topic I have come across, and is a necessary corrective to the often Eurocentric vision of the classics.

Overall, this is a very accessible introduction to the art, and the cultural and political history, of the period. It is eminently readable; pitched to the undergraduate student (including an immensely useful updated bibliographical guide), it is approachable enough for the general reader, and would likely be the kind of book I would recommend to an enthusiastic sixth-former. The illustrations are well-chosen, and the supplementary material is an added bonus: several maps of the empire at the beginning, and a detailed timeline at the end are hugely valuable assets for any ancient historian or classicist.

Stuart Thomson