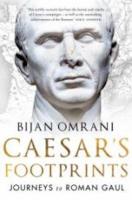

Head of Zeus (2017) h/b 386pp £25.00 (ISBN 9781784970659)

Being Caesar was quite an industry. As a remarkable self-marketer he crafted the story of the great general subduing the abominable threat to Rome, its security and culture; the intrepid pioneer in a terra quite horribly incognita; saviour of the Republic and Romaniser of those who could turn out to be a bit tricky if you weren’t careful.

Of course, the cover has been blown, and in O.’s book we follow Caesar as he fulfils debt-ridden ambitions on his genocidal progress (1.2 million slaughtered, not including others sold into slavery or the collateral dead) through Gaul. On this journey O. touches on geography, biography, topography, history and historiography, etymology, archaeology, anthropology, theology, rhetoric, but all with such lightness as to leave you feeling this is quite normal for an historical travel companion. Then, emerging from Caesar’s depredations is Roman Gaul, with all the advantages of globalisation, and a concept so espoused by politicians, left and right, ever since. The Germanic Franks, of course, get a bit of a look-in later on, but the poor old Gauls remain suppressed until the Celtic revival of the late 18th to 19th centuries, that hugely romantic view based on the good, solid foundations of Ossian (!).

O. is particularly good on Caesar’s attacks on Britain. Nobody wanted to read commentaries on the boring necessity of the consolidation of Roman gains in Gaul, so try this new and ever more exotic conquest to chew over, with a twenty-day public thanksgiving in Rome for all your trouble.

Here, then, is the remarkable development of Roman Gaul and its increasingly full participation in the social, political, cultural, linguistic and religious life of the empire. There are references to the later history of France and its reinvention of itself, but the bulk of the story ends with the fall of the West and the breaking up of marble buildings, and their decoration, for hard-core.

O.’s almost picaresque approach creates opportunities for beautiful descriptive passages, mostly of what you see now when you do the various sites. It also allows for some wonderful diversions, such as the regulations associated with the post of flamen dialis once proposed for Caesar: a prohibition on knots in the fabric of one’s dress, the required secret disposal of nail clippings, and the absolute taboo of looking on a dead body.

And yet, for all the varied and detailed cover, the whole things hangs together beautifully. You don’t feel distracted on your journey through the establishment and development of Caesar’s Gaul, accompanied by your wise, kindly and fascinating guide.

Adrian Spooner