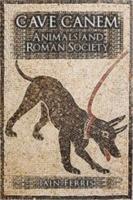

Amberley (2018) h/b 320pp £20 (ISBN 97814456 52931)

F. is by profession an archaeologist who now writes regularly about a range of cultural themes related to Roman civilisation. In this book he examines the role that animals played in Roman society. By this he means primarily Rome itself but takes examples where available from any part of the Romanised world. His sources are literary, epigraphical, pictorial and occasionally archaeological. His stated target audience are undergraduates engaged in classical studies—many, one suspects, from the USA.

He divides his study into sections: animals as pets, animals as workers, animals as food; animals as spectacles, animals in religion and augury; animals as symbols. Each section is mainly expository, with pictorial elements being fully described, though the clarity of the exposition is occasionally interrupted by a willingness to digress. He points out some areas of academic disagreement but rarely seeks to resolve them. He is careful to emphasise that the Romanised world was very large and that overall generalisations are dangerous. The text is supplemented by 100 coloured illustrations (80 taken by the author), concentrated in thirty pages in the middle of the book—which makes cross referencing a bit fiddly—and, at up to five illustrations per page, sometimes too small readily to identify the details referred to in the text. The illustrations are also much more Rome-centric than the text.

What is perhaps most striking is the similarity of the relationships he describes to those that we know today. A study of the role of animals in the British Empire up to 1950 would deliver a similar range of anecdotes and art. Admittedly there would be little about sacrifice and augury, but that arguably says more about changes in religious practices than about changes in attitudes to animals. The examples of using animals to kill or hurt for pleasure would be less pronounced, and it is on this that F. bases the main premise of this text: that the Emperors deliberately employed gratuitous and extensive cruelty to animals as a public relations tool—‘the commodification of the animal world’—and, by doing so, tainted the moral integrity of their authority— ‘psychic damage’. His presentation of this theme is perhaps the least persuasive element of the book.

F. is clearly aware that animal rights have more recently become a major issue, particularly on campus, and the text is dotted with paragraphs expressing, no doubt sincerely, disgust at various Roman practices when seen from a current perspective—probably sufficient to prevent him from being ‘no-platformed’ in California.

Overall this is a competent introduction to an unfamiliar aspect of Roman life, which will undoubtedly increase the knowledge base of its target audience.

Roger Barnes