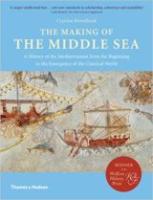

Thames and Hudson (2013) h/b 672pp £34.95 (ISBN 9780500051764)

This is without doubt a very important book. Moving on from the studies of Braudel (1949), Horden & Purcell (2000) and Abulafia (2012), it takes in the 5 million or so years from the Mediterranean’s physical formation to the emergence of the classical world. B. moves with total assurance from geology to archaeology (his own speciality) and any number of related disciplines, bringing life to even the most technical topics in a style of great ease and clarity. Everything is treated as history (no ‘prehistory’ here); with its 387 illustrations (49 in colour), maps and tables, it all adds up to a fascinating story, beautifully told.

Chapter 1 takes us straight into fieldwork on Kythera: ‘Out here, the only sound is the clink of wind-sculpted splinters of limestone on others half-buried in the earth’—unusual first words for a substantial work of scholarship. This and Chapter 2 set the geological scene. Chapter 3 covers the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic (1.8 million to 50,000 years ago), Chapter 4 takes us up to 10,000 BC, with the emergence of hunter-gatherers, fishers and early agriculturalists at the region’s eastern end. Now men were, cautiously, beginning to take to the sea. In Chapter 5 (Neolithic, 10,000 to 5500 BC), farming is spreading and islands begin to be settled; Cypriot and Levantine societies emerge. The sixth chapter (‘How It Might Have Been’) deals with the comparatively obscure period of 5500 to 3500 BC. Chapters 7 to 9 move confidently into the Bronze and early Iron Ages (3500 to 800 BC), more familiar territory perhaps for both classicists and general readers. In Chapter 10 (‘The End of the Beginning’) B. leads us into the age of literacy (800 to 500 BC), and the beginnings of Greek predominance in the Aegean, not to mention the rise of Carthaginian and Etruscan influence

B. ends with four questions on later Mediterranean history: 1. How did Mediterranean empires arise? 2. Why were its societies so successful in expanding beyond the basin? 3. Why did Greek materials, habits and attitudes become common currency around the sea? 4. Why did the Mediterranean witness so many world-changing conceptual and religious breakthroughs in the area of relations between the individual, society, and the transcendent? This is all in keeping with the undogmatic tone of the rest of the book.

Throughout, B. is concerned to avoid any kind of historicist narrative. He tells a tale of diversity, of flourishing and decline: ‘We…explore a multitude of streams, as some headed elsewhere or ran dry, while others began to flow in parallel, converge, and finally blend into a stronger current.’ He likes to talk of cultural strands being braided together and then loosening. Conclusions are suggested provocatively but with modesty. The breadth of his scholarship, his lively curiosity and insights, and his analysis of vast amounts of data, add up to a stunningly original tour de force.

At less than £35 for 600 beautifully produced pages it’s a snip. And readers outside the confines of academe should seize on it with cries of joy. It’s what scholarship ought to look like.

Anthony Verity

NB: The Making of the Middle Sea will be published in paperback on 31st August 2015, priced £24.95.