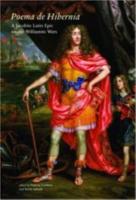

Irish Manuscripts Commission, Dublin (2018) 563pp £40.05 (ISBN 9781906856597)

Here is a beautifully produced edition and translation of a 17th-century Latin epic on one of the most dramatic periods in Ireland’s history. This long poem was written to support the case of the exiled Stuart King James II of England and Ireland. More precisely, it is a contemporary account of the events between Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland and the end of the Williamite wars in 1691 (the Catholic James II versus the Protestant William of Orange). The volume is a fruit of an interdisciplinary collaboration between the classicist Keith Sidwell and the military historian Pádraig Lenihan.

The edited poem consists of six books and comprises just a little over 5,500 lines of dactylic hexameter. It should be noted that the poem, composed sometime between November 1691 and June 1693, survives in a single manuscript (Gilbert MS 141 in the Dublin City Archive, plus one copy). Its title is derived from the words inscribed on the manuscript’s spine, seemingly a mere description of the poem’s contents and not its intended title. The author’s name is unknown, but already in the poem’s first book it is made clear that the poet is an ardent Jacobite and a zealous Catholic.

The first three books of the poem sketch the historical background to the Irish-English conflict, starting with Oliver Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland in 1649. The sixth and final book ends with the capitulation of the Irish forces and their departure for France. As S. and L. explain in their introduction, the poem is best understood as a political document.

To identify the poem’s author has been one of the most difficult tasks for the editors. Some clues are provided. For example, the author of the Poema mentions his imprisonment in the aftermath of the second siege of Limerick. There are indications that the poem was penned by Thomas Nugent, who was chief justice of King’s Bench under James II and who in fact was attainted in 1691. In addition, there are numerous references to the Nugent family throughout the poem. There is nonetheless one major problem in stating definitely that Thomas Nugent was the poem’s writer. Nugent was a firm supporter of Tyrconnell, who after the Battle of the Boyne planned to make terms with William of Orange, something that seems to fly in the face of the poem’s laudatory passages about Tyrconnell’s main opponent Patrick Sarsfield. Through a thorough investigation of Thomas Nugent’s political situation, the editors offer a good explanation of how this Jacobite still could have been the writer. That said, the poem is a fascinating political tract and also a personal account of a high-up official working for the exiled king (regardless of whether Nugent was the author or not).

The volume has required the editors’ close collaboration. L.’s profound knowledge of Ireland’s early modern history has been essential for understanding the text in its immediate historical circumstances, while S.’s vast expertise in the field of Latin literature and his editorial experience have been crucial for tackling literary and textual issues.

As the readers of this website have a particular interest in the history of Latin literature, let us look at some of the text’s literary and linguistic peculiarities. Much of the work behind the volume belongs in neo-Latin studies, a relatively new scholarly field that is concerned with Latin writings produced in the period between the dawn of the Renaissance to the 19th century. Humanist writers such as the author of the Poema considered mediaeval Latin to be corrupt, and they therefore turned to the models provided by classical Latin literature. As his fellow writers on the continent, the author of the Poema is highly classical in his language and style. He finds his inspiration in epic poets from all periods of classical Latin literature, including Vergil, Lucan, and Claudian, to name a few. Yet the reader will quickly realise that the Poema is not a soulless recycling of ancient prototypes, but a clever reuse of the exemplary texts. Illustrative is the case of the author’s imitation of passages from Lucan’s De Bello Civili when treating gruesome episodes from the Williamite wars. Lucan offered a useful pattern of imitation not only because of his very characteristic language known for its drastic similes, but also because the pro-Irish author must have seen a deal of similarities between the political situation described by Lucan and his own reality.

As is remarked in the introduction, the author of the Poema sometimes deviates from classical language usage. This is found, for instance, in his inventions and borrowings of neologisms to describe phenomena that did not exist in the ancient times, particularly as regards the technical terms relating to warfare. Thus, the poet uses archithalassa for ‘flag-ship’, derived from the already existing neo-Latin word archithalassus (‘admiral’).

Sidwell’s philological expertise and knowledge of Latin texts that cover the literature of classical antiquity, of mediaeval times and of the early modern era evokes admiration and envy in everyone who works with neo-Latin texts, and his translation is a delight to read. It will suffice to quote a heart-wrenching passage from the poem’s final book, where the poet describes how Irish families are divided by the decision to leave Ireland (best appreciated when read aloud):

Here brother brother leaves, scarce opening

His lips, and headlong casts just one ‘Farewell!’:

The rest grief hides. And as Andromache

Had mourned her son Astyanax, thrown down

From tower high to solid earth, just like

A second Niobe, who did bewail

Her children’s deaths, a mother now bereft

Of offspring, almost turned to rock, does weep

And cries aloud: ‘O Woe! Misery me!

Why did I, fecund, bear so many griefs,

Ill fertile for my woes and many falls!

Why did Lucina midwife for my pangs,

And sudden Fates not break the starting threads?

Why am I called by neighbours happy in

My labours? Why did lightning-bolts not make

Me silently abort? Why did I not

Receive from nature sterile years? Indeed,

Why did she even suffer me t’exist

And life possess? Thus better had I been

With Chaos and the prior nothingness

Commingled, thus existed never, thus

Not ever been exposed to Fate at all.

Thou, highest maker of the universe,

To whom alone of all is glory owed,

Call forth the praises from our throats and have

These men return, restore them to those homes

From which their comrades’ infamous deceit

Has caused their flight.’

Deserit hic fratrem frater vixque ora recludit

Præcipitatque ‘Vale’ semel: abdit cætera Mæror.

Jam velut Astyanacta suum de turre cadentem

Luxerat Andromache, Niobe velut altera deflens

Funera Natorum, flet (vix non saxea) mater

Pignoribus spoliata suis et: ‘Cur ego’ clamat,

‘Tot mihi, Væ miseræ, peperi fæcunda dolores,

In luctus malè fœta meos pluresque ruinas?

Cur Lucina meo est obstetricata Labori

Orsaque non subitæ ruperunt Stamina Parcæ?

Cur sum Vicinis ego dicta puerpera fœlix

Curve mihi tacitum non fecit Fulgur Abortum?

Cur mihi non steriles Natura impertijt annos?

Immo cur dedit Esse mihi Vitaque potiri?

Sic melius permista Chao Nihilque priori

Sic ego nulla forem, sic non obnoxia Fatis.

A Tu, Summe Sator Rerum, cui Gloria Soli

Debetur, nostris e faucibus elice laudes

Atque hoc fac reduces et redde Penatibus ijsdem,

A quibus infami Sociorum fraude fugantur.’

Elena Dahlberg (PhD in Latin) is a postdoctoral researcher at Uppsala University, Sweden. Her own scholarship concerns neo-Latin literature in the area around the Baltic Sea.