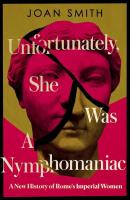

William Collins (2024) h/b 292pp £25.00 (ISBN 9780008638801)

The provocative title of this book is not a deliberately eye-catching take on ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore’, but rather a direct quotation from an Italian tour guide overheard by the author as he described Augustus’ daughter, Julia, in the empress Livia’s celebrated Garden Room, now displayed in Rome’s Palazzo Massimo Museum. Such casual acceptance of what S. passionately believes to be ancient calumnies is not confined to Italy (S. cites at least one label in London’s British Museum) or even to tour guides (she regularly takes issue with contemporary popular historians such as Mary Beard and Tom Holland), and, as they devour the pages of this landmark book, most readers (the present reviewer included) will realize that their own view of the Julio-Claudian elite has been shaped by centuries of assumptions based upon little but salacious and misogynistic tittle-tattle.

Instead, S. argues convincingly and passionately that our readings of (always male) Roman historians should be ‘informed by what we now know of the mechanics of domestic abuse’—and, an enthusiastic Latinist, since S. served as Co-Chair of the Mayor of London’s Violence Against Women and Girls Board from 2013 to 2021, she knows whereof she writes. And how she writes! Being also a journalist, she knows how to make words fly off the page. But the picture she reveals is grim.

Married very young, most imperial women were prematurely sexualized as pre-pubescent girls, trafficked as brides without their consent to much older men and often used as pawns in the game of Roman politics. Their husbands were often abusive. From Augustus (who effectively raped his future wife, the already pregnant nineteen-year-old Livia) and Tiberius (who, ‘like other men who have tormented and murdered female relatives, … flung outlandish accusations against [Agrippina the Elder], trying to sully her memory’) to Nero (who kicked his pregnant wife to death), the Julio-Claudians emerge as vengeful, violent, petulant dictators, unscrupulously manipulating and thwarting often intelligent, determined women to suit their own ends.

Each chapter is prefaced by a brief biography of its major players (invariably ending with their violent deaths) and, as she catalogues the fates of many of these women, S. brings the period shockingly alive in a way that few other histories achieve—not just the flesh-creepingly exploitative perversions of Capri, where Tiberius and Caligula fed one another’s depravity like first-century Jeffrey Epsteins, but the calculatedly political manipulations of Claudius’ self-serving freedmen as they choreographed the fates of Messalina and Agrippina, a woman whom S. does not seek to condone but rather to understand, her ‘emotions blunted by the terrible series of losses she experienced as a young woman. It would have taken several generations of violent deaths to produce a woman like Agrippina, able to put aside normal human feelings in her single-minded determination not to meet the same fate as her female ancestors.’

As can be seen from the last sentence, S. does not seek to whitewash her female subjects. She is, for example, quite prepared to admit that Agrippina schemed to marry Nero and that she may have been responsible for some (but certainly not all) of the deaths laid at her door, but as she observes, ‘the imbalance between Agrippina’s supposed “victims” and the hundreds of men killed on the orders of Claudius is striking.’ Julio-Claudian men, she insists, were significantly more amoral and immoral than Julio-Claudian women, yet history has whitewashed the one and vilified the other. This book, then, seeks to address these double standards and redress the balance, and it succeeds brilliantly.

While some readers may feel that S. occasionally goes too far, her revisionist history is a timely antidote not just to the modern trend of seeking to rehabilitate such vicious men as Tiberius, Claudius and Nero, but to the lazy historical fiction of (for example) I, Claudius. Presenting Rome’s imperial family as real, three-dimensional people, it makes no bones about the world that they inhabited. It is the most compelling account of the period that this reviewer has encountered. So, even if you don’t agree with its conclusions, read it!

Note This review is based on a pre-publication uncorrected proof, in which illustrations appeared in black and white within the body of the text, and, while a dramatis personae and endnotes were included, the index was yet to be collated.

David Stuttard