In this article, I propose to analyse why I believe that Clytemnestra should be a more celebrated figure of what it means to be a woman in feminist receptions of the Homeric epics than her cousin Penelope. To do this, I will deconstruct and comment on the virtues of Penelope and how we may see these as anachronistic values of the moral goodness of women. By contrast, I will analyse the vices of Clytemnestra’s character under a feminist lens, thus concluding how her violence and aggression makes her a powerful symbol of femininity that still resonates with those who read about her today.

Before we look at Clytemnestra, we must first understand where Penelope’s shining reputation comes from. In Book 11 of the Odyssey, Odysseus visits the Underworld and finds Agamemnon dead. Upon talking to the shade of his former comrade, Odysseus learns that Agamemnon was killed by his wife, Clytemnestra, when he returned from the Trojan war. As a result of this, Agamemnon bitterly shares that women are no longer to be trusted, although he compliments Odysseus on the loyalty of his own wife, the lovely and loyal Penelope. Effectively, through praising her, Agamemnon singles Penelope out against all others of her sex, who are deemed untrustworthy and calculating, thus immortalising Penelope as the one woman who can still be trusted. It seems odd, however, that – at other parts of the epic – Penelope is praised for her intelligence, which may have otherwise been deemed as trickery and deceit akin to that of her cousin. We are told during the early books of the Odyssey that Penelope plays a trick on the suitors to prevent them from marrying her, by weaving a shroud for Odysseus’ father which she unpicks every night by candlelight. We must question here why this act has been dubbed as loyalty throughout history, rather than being seen as deceit.

Penelope’s image being reduced to just her fidelity has caused some discomfort among modern classicists. Penelope’s loyalty to Odysseus comes at the cost of her status – the Queen of Ithaca (a figure that should be commanding) becomes reduced to a figure that is pursued for the pleasure of the insolent suitors, thus rendering her almost servile in her loyalty to Odysseus. She becomes reclusive, and the power of Odysseus becomes adopted by the suitors, who destroy the palace. Through deconstructing the text in this manner, we learn that Penelope’s loyalty to Odysseus is akin to the loyalty Eumaeus has for his master, an image that presents Penelope as a victim of the patriarchal bonds of marriage.

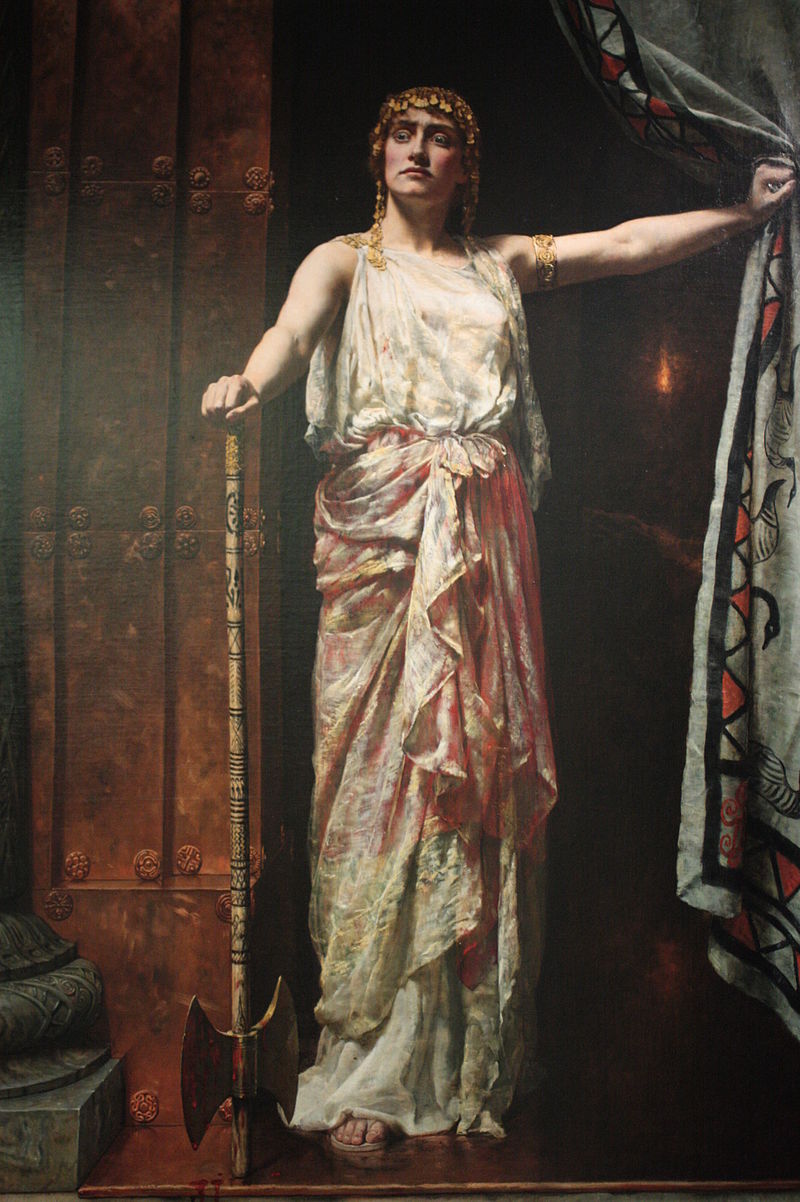

Now, we turn to Clytemnestra, who acts as the dichotomy to Penelope. Where Penelope is powerless in her loyalty to Odysseus, Clytemnestra becomes powerful and calculating in Agamemnon’s absence. The dichotomy of character is further emphasised in Book 11, in which Clytemnestra is dubbed as evil and untrustworthy, while Penelope is described as the most loyal of women. In short, because Agamemnon sees Penelope in such a positive light, Clytemnestra is automatically seen negatively. It is interesting that the only statement on the morality of Clytemnestra that we get comes from the shade of the man she wronged, thus implicitly encouraging audiences to form the same conceptions of Clytemnestra’s actions. I wonder if the responses to Clytemnestra’s crimes would differ if we learnt of them from a neutral character.

I am now going to offer an alternative view of Clytemnestra’s crimes against her husband. To fairly understand Clytemnestra’s extreme act of murder, we must consider that the murder of Agamemnon was an act of retribution from a grieving mother to the man who took her child’s life. Sources on Iphigenia (the firstborn daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra) differ in their outcome, but all agree that Agamemnon led his daughter to be sacrificed to appease the maiden goddess Artemis to secure the Myrmidons a fair wind for their voyage to Troy. Images of Clytemnestra cradling the bloodless body of her favourite child haunt the cruelty of her actions, thus somewhat neutralising the sting of the crimes she commits. Because of this, we can begin to reframe our thoughts on the actions of Clytemnestra; what was once seen as a terrible act of treason becomes a brutal act of retribution, and ultimately female liberation, thus endowing Clytemnestra with a great amount of her own kleos that long outlasts Penelope’s. In other words, the woman who was once stripped of her femininity and villainised, becomes an archetype of women’s liberation against systems of patriarchal oppression.

Overall, though Penelope’s enduring image as a model wife gave her kleos in the ancient world, it is Clytemnestra’s brutal victory over the patriarchal society of Homer that makes her a more appealing heroine to modern readers of the epics. Unlike her cousin, Clytemnestra refuses to be seen only as a wife, and – through murdering Agamemnon – becomes the acclaimed destructor of the patriarchal bounds which wives in the ancient world were restricted by. This defiant and subversive figure of women’s liberation is much more of a welcome figure in our modern age of female power, thus making Clytemnestra a hero in her own right, outside of Penelope’s more classically virtuous shadow.

More About the Author...

Name: Em Miles

University: University of Liverpool

Favourite classical figure (real or mythological!): Dionysus

Favourite classical subject: Religion, tragedy and literature

Favourite piece of classical reception: I love books, especially retellings that provide voices to previously outspoken women of antiquity

What inspired you to write this piece for the Rostra?

I was inspired to write this piece as I’ve always felt a level of discomfort from the way that Penelope has been seen as this great figure of moral superiority, when clearly she was being oppressed by the constraints of her fidelity. It was this discomfort, alongside my perception of Clytemnestra as a radical defendant of female power, that inspired me to write a piece, showing how far Classics has moved away from the anachronistic ideas of women being seen as only morally good if they conform to patriarchal systems.

What do you think is the biggest benefit of learning about Classics? Why should someone get into Classics?

For me, the biggest benefit of studying Classics has been the lessons it has taught me about our own time. Through studying the texts of antiquity and the reception of them, we learn so much about what it means to be human, and what this would have meant for those living millenia ago – we learn that, in reality, we are not that different to our ancestors.

If you’ve previously interacted with Classics for All, what impact has it had on your studies/interests/etc.?

The opportunities I have gotten from Classics for All through The Chorus have had a huge impact on me as a young Classicist. The ability to interact with world renowned authors and translators – such as Jennifer Saint and Emily Wilson – have been invaluable to me, as have the opportunities to write for The Rostra. Knowing that I’m a part of a rich community of young people who are as passionate about Classics as I am makes me incredibly excited for the future of the subject and the future of scholarship in Classics – we are here, we are vibrant, and we are excited to be contributing to such an amazing field of study!