Few people would expect ancient Greece and ancient Japan to have similar creation myths. Not only do their creation stories have thematic parallels, but the way the stories were recorded shows that these two island nations have more of a culture coalition than we might think.

The ancient Greek creation story was recorded by Hesiod in his epic poems ‘Theogony' and ‘Works and Days’, around 650-750 BCE. The primordial deity Chaos was the first thing to exist – a personification of the darkness that preceded the creation of the universe. Next, the primordial deities sprang into existence, including Gaea (the earth), Tartarus (the underworld), and Eros (love). Gaea then gave birth to Uranus (the sky), who became her mate. Together, Gaea and Uranus gave birth to the Titans, the Cyclopes, and the Hecatoncheires. The youngest of the Titans, Cronus (time) castrated his father and took his place as the ruler of the universe. He threw Uranus’ genitals into the sea from which came Aphrodite (goddess of love, beauty, and sexuality). Later, Cronus swallowed his children to prevent them from overthrowing him, but Zeus was saved and grew up to overthrow Cronus and become the king of the gods. With the world now under his rule, Zeus created humans, who were mortal and subject to the whims of the gods. Hesiod’s creation story emphasises the chaotic nature of the world's beginnings and the role of divine intervention in the course of history.

On the other hand, ancient Japan's creation story was recorded in a book called the Kojiki at the beginning of the Nara period (710-794 CE). This book is the oldest book of Japanese history and was written nearly one and a half millennia after Hesiod – that’s equivalent to the gap between us and the fall of Rome! The narrative begins with the supreme deity, Ame-no-Minakunushi (master mighty centre of Heaven), appearing from nothingness. Ame-no-Minakunushi is a god of the sky and the ruler of all other gods in the Shinto religion and has no physical form or gender.

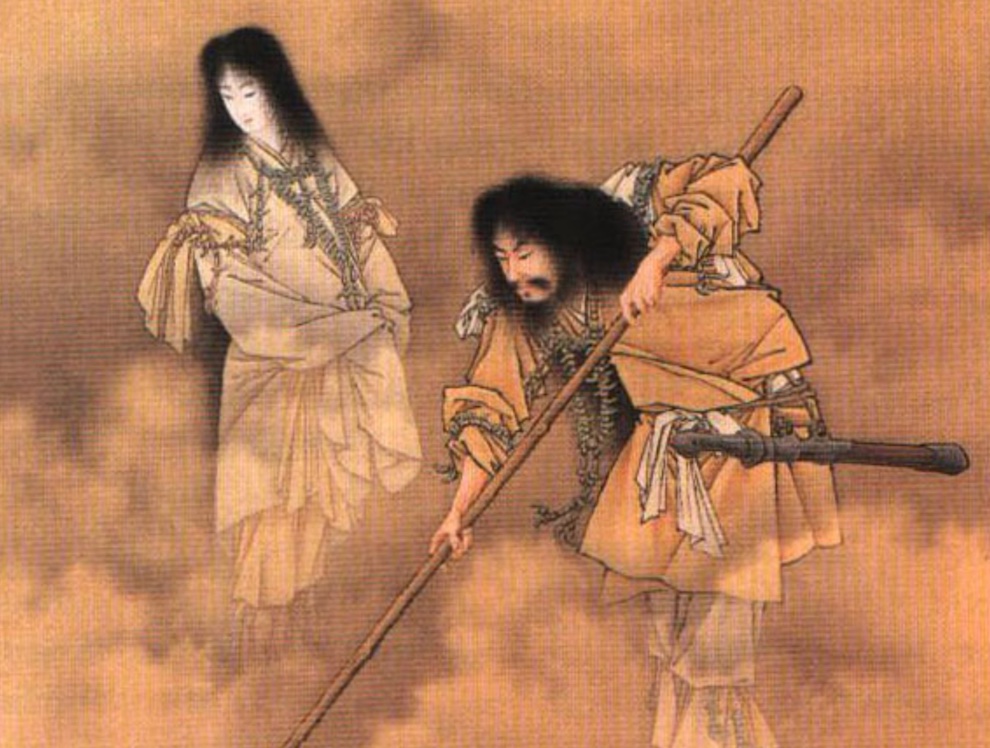

According to the Kojiki, the world was created by two deities, Izanagi (he who beckons) and Izanami (she who beckons). They were sent by Ame-no-Minakunushi to create the islands of Japan, which at that time were just a mass of water. They threw a 'spear of heaven' into the water and the droplets that fell from the spear tip formed the first island of Japan, Onogoro. The Kojiki creation story reflects the ancient Japanese belief in the power of the natural world and the importance of the gods in shaping it.

There are many similarities between the creation stories of ancient Greece and ancient Japan. In both traditions, the universe begins from a formless or empty void. In ‘Theogony’ and ‘Works and Days’, it was Chaos, and in the Kojiki, it was nothingness.

Another similarity between the two creation stories is the role of the first gods in creating the world. In the Greek creation story, the world is created by the Titans. Similarly, in the Japanese story, Izanagi and Izanami created the islands of Japan and the gods that populate it. In both stories, the gods are depicted as powerful beings who shape the natural world and control the elements. They are often personified as anthropomorphic deities, with human-like characteristics and personalities. The Titans are associated with different natural elements, such as Oceanus (the sea) and Hyperion (the sun). Similarly, in the Japanese creation story, there are deities including Amaterasu (the sun goddess) and Susanoo (the storm god). This reflects the ancient belief that the natural world was inhabited by powerful spiritual forces that could influence human life.

One intriguing parallel between the Greek and Japanese creation stories is the theme of generative power and the creation of new life through the act of throwing genitals into the water. In the Greek creation story, the god Cronus castrates his father Uranus and throws his genitals into the sea. Similarly, in the Kojiki, the 'spear of heaven' is described as a spear from which 'two testicular jewels dangle'. This parallel suggests a common cultural motif. It also hints at the idea of creation through transformation and metamorphosis, as the discarded genitals or the drops from the spear give rise to new life.

While both creation stories involve the actions of powerful gods creating the world, there are some key differences between the two. For example, in Greek mythology, there are numerous gods and goddesses who play a role in the creation of the world and its inhabitants. In contrast, the Japanese creation story focuses on a smaller number of gods and goddesses. Additionally, the Greek story is focused on the creation of the earth and sky, while the Japanese story is focused on the creation of specific islands.

While both the Greek and Japanese creation stories have a religious significance, they are embedded in different religious traditions. The Greek creation story is part of Greek mythology and is closely linked to the religious practices of ancient Greeks, while the Japanese creation story is part of Shinto mythology and is associated with the religious practices of Japan. There is no direct evidence to suggest that the Greek creation story directly influenced the Japanese creation story. The two cultures were geographically distant and had little direct contact with each other. However, it is possible that both stories were influenced by common themes and motifs found in other ancient creation myths.

Hesiod’s poems ordered the various myths of Greek mythology into a cohesive timeline. This helped to create an understanding of the myths for all Greeks, beginning with the creation story. Similarly, the Kojiki acted as a record of archaic Japanese words that were derived from Chinese-style characters, making them more accessible to domestic readers. Both texts have a common purpose: to serve the interests of the people of their respective lands. By recording and organising their cultural histories, these texts allowed for a deeper understanding of their heritage and remain enduring monuments to the power of myth and storytelling in our quest for knowledge and meaning.

Humans have always been interested in creating new theories about the origins of the world and why and how we came to exist – from Charles Darwin's ‘Theory of Evolution’ to Georges Lemaître's ‘Big Bang Theory’. These explanations not only offer us comfort, but also reaffirm our connection to the world around us. It’s this curiosity that propels us forward to think about our existence and about how we came to be. And it is the same drive that underpins the study of classics. Without our questioning of existence and creation, we would not have been driven to research and uncover the modern civilizations of Greece and Rome. It is only when we ask ourselves how we came to be that we go in search of knowledge.

Laila Omar Abbas studies classics as a pathway at Leyton Sixth Form College. She has taken a keen interest in comparing different ancient civilisations to see if there is more to the story of human history than we know. Studying ancient Greek mythology has proven invaluable to Laila as she explores the intricate connections between literature, films, and historical eras, illuminating a rich tapestry of human civilisation.