A portal to another world

Throughout my life and university career, I have gradually come to realise that whispers of the ancient world can be heard everywhere.

Growing up, my first encounter with the ancient world was The Roman Mysteries by Caroline Lawrence. This seventeen-part book series follows four children, Flavia, Nubia, Jonathan and Lupus, as they undergo various adventures in Rome (and further afield) to solve detective cases. These books were very engaging and accessible, with little bits of Latin language here and there, and a lot of Roman history. This ignited my interest in classics and spurred me on to choose Latin and classics as subjects at secondary school. I often wonder, would I have chosen to study the ancient world if I hadn’t already engaged with it through fiction, where it was portrayed as fun and exciting? Would I have expected classics lessons to involve learning an old language, reciting poetry I could not relate to, and studying individuals who were no longer important? Maybe.

I was fortunate enough to attend a state school that offered classical civilisation and Latin for both GCSE and A Level. This nurtured my love and knowledge of the ancient world and gave me the confidence to pursue it at university. I attended the University of Birmingham and studied BA ancient history. I loved my time there as there was such a wide range of modules, covering Egypt and Mesopotamia, as well as Greece and Rome. There was no prior knowledge needed to study and enjoy the degree, so whilst my formal education in classics and ancient history was useful, it was by no means a prerequisite to the course. Despite this, I know it can be daunting to go to university to study something you have never encountered before. However, you may have had more interaction with the classical world outside of the classroom than you think.

It was not until I had graduated straight into a pandemic and lockdown had begun, that I started to notice the role of classics in popular culture. This was because I found myself gravitating towards books and films from my childhood for much-needed comfort. I noticed that all of my old favourites had a very common thread. Whether it was the Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis, the Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, or Percy Jackson by Rick Riordan, classical influences could be found everywhere and had been influencing me for much longer than I originally thought.

I started to think more and more about the way in which we engage with the classical world through fiction and media as children, how this shapes our perception of the ancient world, and what the impact of this ultimately is on future researchers.

When I returned to university for my master’s degree, I knew I wanted to research classical reception in children’s literature. My focus was on classical reception in The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis. As one of the fathers of fantasy, alongside J.R.R. Tolkien, his classical education influenced his own writing, the fantasy genre, and children’s perception of the classical world as a result.

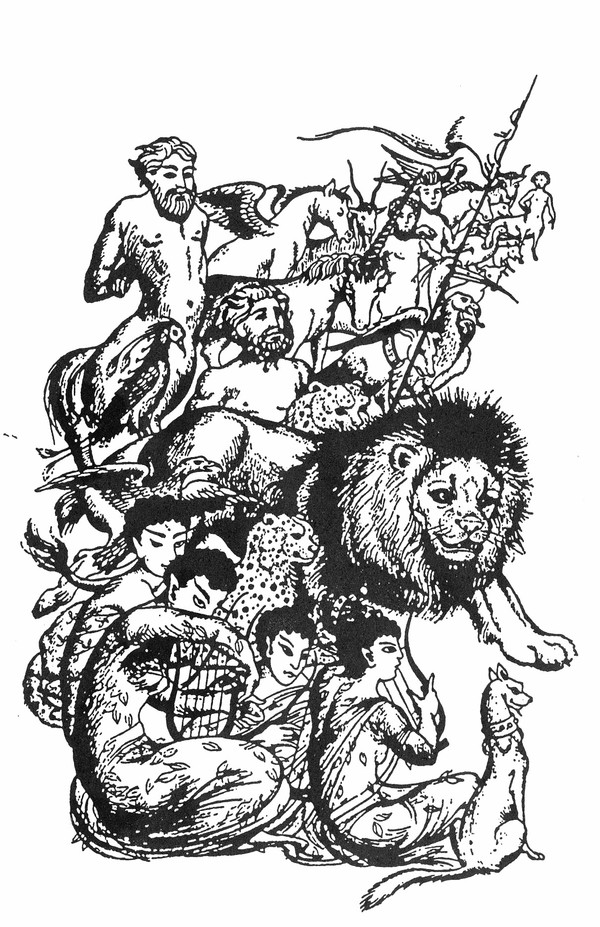

Whilst it is difficult to summarise a dissertation in a sentence or two, it is safe to say there are a lot of classical elements in the Narnia books! These range from mythological creatures like centaurs and nymphs to plot lines inspired by Homer’s Odyssey and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. My specific focus was on the use of classical metamorphoses and how it is used to explore religious transformation.

C.S. Lewis was a Christian who came to religion later in life and felt Graeco-Roman mythology was the ‘childhood of religion’ [1]. Therefore, it is often argued that he used it in his works as an allegory for Christianity [2].

One scene in particular, in Prince Caspian (the second book in the Chronicles), shows how Lewis viewed the classical world through this lens of Christianity. In this story, the classical elements and creatures, as well as Aslan (an allegorical Christ-like figure) have been absent under the reign of the Telmarines who disregard them as merely myth. Towards the end of the book, the classical characters return in triumph and defeat the Telmarines. In this episode, the classical world returns in full force, arguably as a metaphor for the return of religion. By using pagan imagery to support his Christian allegory, Lewis is associating this nostalgia for a distant, more magical past with his own theology.

Whilst the classical world is portrayed in a generally positive light here, it is interesting to note the inclusion of one individual – Bacchus. The god of wine and revelry takes part in this parade and is described as ‘a youth, dressed only in fawn-skin, with vine leaves wreathed in his curly hair. His face would have been almost too pretty for a boy, if it had looked not so extremely wild’ [3]. Later on, the character of Susan says, ‘I wouldn’t have felt safe with Bacchus and all his wild girls if we’d met them without Aslan’ [4]. If it is understood that Aslan is a parallel for Christ and the Narnians for Christians, this can be interpreted as Lewis saying paganism is acceptable to observe, but not ‘safe’ without Christ by your side.

My research has taught me how the classical world can be used and adapted in literature to serve different purposes. It is especially important in children’s literature as it is nearly always didactic and, as someone’s first interaction with the ancient world potentially, it functions as a doorway into classics! How it is portrayed is important. Like all pieces of literature, it is influenced by the author and the author in turn influences the reader. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the author and the time period they were, or are, writing in as this can help us think critically about what we are reading and absorbing.

The questions I ask myself when analysing a piece of classical reception are:

- What classical elements are there in these works?

- How have these been interpreted and adapted to say something new?

- What is the impact of this on the reader’s understanding of classics?

These questions are important, particularly since classics is not yet widely taught in schools. As a result, one of the primary avenues through which people engage with the ancient world is through fiction, film and other media. By looking at children’s literature specifically, we can gain a better understanding of how people interact with the classical world and what the impact of this is. With there being so many misconceptions and misuses of the ancient world, children’s books can be a powerful tool for learning and a way of addressing issues within the discipline.

One of the great things about classical reception studies is that it is a seemingly endless field which changes every day! Embarking on my master’s degree was the best decision I ever made. I felt I really grew as a researcher and I loved being able to specialise more. I improved my communication and research skills, as well as my ability to think creatively and take on constructive criticism. Now, I’m working in communications at the University of Birmingham and get to help shine a spotlight on the amazing research the university does. I hope one day to return to academia and complete a PhD, focusing once more on classical reception in children’s fantasy literature. Until then, there are so many ways to get involved with the classical world and I take great comfort in knowing it can be found everywhere - if you look for it!

[1] Lewis 1955: 221.

[2] Duriez 2004: 36; Walsh 1979: 131, 140.

[3] Lewis 1951: 137.

[4] Lewis 1951: 138.

Bibliography:

Duriez, C. 2004. A Field Guide to Narnia. London.

Lewis, C.S. 1951. Prince Caspian. London.

Lewis, C.S. 1955. Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life. London.

Walsh, C. 1979. The Literary Legacy of C.S. Lewis. London.

Harriet is a recent graduate from the University of Birmingham with a BA and a master’s degree in ancient history and classics. Having worked as an online tutor for four years and now as a staff member at the University of Birmingham, she is passionate about education and making classics more accessible in schools.